In the weeks after recording “A Million Miles (I Love You),” Prince continued to work closely with Sheila Escovedo: adding her drums and percussion to tracks like “God (Love Theme from Purple Rain),” “The Belle of St. Mark,” “Pop Life,” and “17 Days.” They were growing closer in other ways, too–their friendship taking on “increasingly romantic overtones,” Sheila writes in her 2014 memoir The Beat of My Own Drum.1 During the February 7 session for the “God” instrumental, engineer Peggy McCreary remembered the pair “musically just playing with each other, sort of flirting with each other. It was midnight, and I was like, ‘Okay, can’t we just leave? (laughs) Can’t you two just get a room?’”2

But it wasn’t until the evening of Sunday, March 25, that they finally consummated the relationship–figuratively speaking, of course. That night, Sheila arrived at Studio 3 of Sunset Sound to find “sweet-smelling candles burning… Prince had set up the studio like a living room–all comfortable and cozy as if we were at home.”3 Conspicuous in their absence were her drums. “I just saw a mic and I said, ‘Where’s the gear?’” she later recalled. “And he said, ‘We don’t need any. You’re going to sing with me.’”4

I said, ‘Where’s the gear?’ And [Prince] said, ‘We don’t need any. You’re going to sing with me.’

Sheila E.

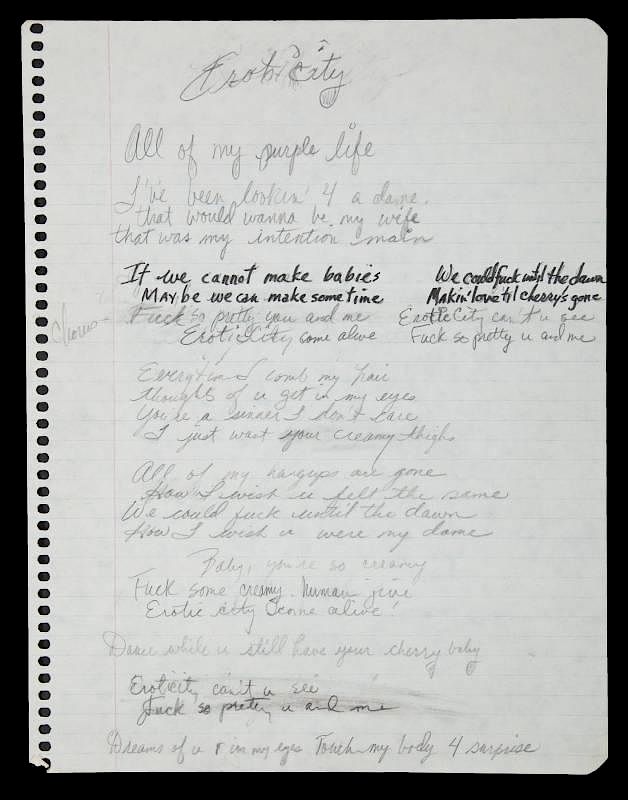

If Sheila was caught off guard by the unplanned duet, she’d be even more surprised once she saw the lyrics. “Erotic City” was Prince’s most explicit song since the halcyon days of 1999: a throwback to the fetishized domestic bliss of “Let’s Pretend We’re Married,” wherein the narrator strays from his quest for “a dame / that would wanna be my wife” in order to sing the praises of purely non-procreative sex. “If we cannot make babies / Maybe we can make some time,” Sheila would sing on the chorus, followed by Prince’s echo: “Fuck so pretty you and me / Erotic City come alive.” Then, back to Sheila: “We could fuck until the dawn / Makin’ love ’til cherry’s gone.” It was this line that would prove the sticking point: “I’m like, ‘Um, that word right there? I’m not going to say that word. You can say it, but I’m not going to say it,’” she recalled.5 In the end, she writes, Prince “worked out a compromise. He would sing[,] ‘We can f— until the dawn’ while I sang[,] ‘We can funk until the dawn.’ 6

Whether Sheila’s account is true, or just a little myth- and modesty-burnishing on her part, the ambiguity between “fuck” and “funk” on the finished track is a key piece of the “Erotic City” legend. It brings to the song a frisson of “did-I-just-hear-that” excitement–not to mention a veneer of plausible deniability, in a time when the “f-word” was still a relatively rare occurrence in mainstream popular music. Recall, for example, that just a few months earlier, Prince had hidden the offending title of “We Can Fuck” by listing it on the studio work order as “The Dawn”: a move that may have obliquely inspired the “Erotic City” line in question. He’d bring things full circle six years later, when “We Can Fuck” finally came out on the Graffiti Bridge soundtrack–now with the more modest, presumably Sheila-approved title “We Can Funk.”

[Prince] worked out a compromise. He would sing ‘We can f— until the dawn’ while I sang ‘We can funk until the dawn.’

Sheila E.

As nasty as its chorus may have been, however, “Erotic City” is best remembered for its even nastier groove. Here, too, Prince seems to hearken back to his electro-funk epics of the 1999 era; but rather than retreading past glories, he does so with a sense of tacit self-one-upsmanship, showing just how far he’d come as a musician and producer in the past two years. He opens the song with a solitary tone bend high on the neck of his guitar: a simulated twinge of arousal. In comes the reverb-drenched drum machine (a LinnDrum, rather than its favored predecessor the LM-1); in fact, the snare samples are reversed so that we hear the reverb first, each hit preceded by an electronic intake of breath. Prince moans over the beat, starting low and growing in intensity as the guitar and bass stir to life beneath him. A throbbing bassline takes the lead for a few measures, joined in short order by some velvety descending keyboard chords. Last comes the stickiest hook of all: a toylike synth line that evokes the sound of a Touch-Tone phone being dialed.

Another, crucial layer of sonic freakiness comes from the track’s pervasive pitch-shifting, the result of an old studio trick from the 1960s. Prince “had discovered that if you put the tape machine down to half speed, you can sing in your normal voice and play guitar, and when you put the tape machine back to regular speed, it’s going to be higher and thinner,” explained engineer Susan Rogers. “He would play the whole song at half the tempo in his normal voice and he’d play guitar parts at half the tempo, and then speed the machine back up.”7 Contrary to popular belief, “Erotic City” wasn’t the first time he’d used this technique; the climactic synth solo of “When Doves Cry” had also been cut at half speed to ensure he played it perfectly. But this was his first experiment with tape speed manipulation as a purely expressive tool, and he duly went nuts with it. The-sped up rhythm guitar defamiliarizes the sound of the instrument, turning his intricate chicken-scratch into a purely percussive element–a gimmick pioneered by, of all groups, KC and the Sunshine Band, on their 1975 hit “Get Down Tonight.” His vocals, meanwhile, are variously sped up and slowed down, creating a trio of distinct personae that recall the harmonizer-assisted God’s and children’s voices from the intro and outro of “1999.”

The first voice we hear is slowed down to a sonorous baritone: moaning the pronoun “I” and murmuring the song’s title as if emerging from a fugue state, then singing the first verse (“All of my purple life…”) like a tranquilized Larry Graham. When the chorus hits, Prince’s vocals snap back to regular speed (or close to it, anyway), delivering the call-and-response with Sheila in a slightly sped-up approximation of his natural register. This “normal” voice retains the lead for the second verse (“Everytime I comb my hair…”), doubled by the baritone; on the third verse (“All of my hangups are gone…”), they’re joined by yet another, helium-pitched vocal singing high harmony. Both altered voices continue to pipe up throughout the song like a Greek chorus: the low one with sluggish interjections of post-coital somnolence (“Baby, you’re so… creamy”); the high one running laps of the libido, Prince’s own Imp of the Perverse. The overall effect is like a Victorian cross-section of the mind of a satyriac: A Freudian trinity with three different ids, or, for my younger readers, an Inside Out crew where every emotion is a variation on “horny.”

I went to see [George Clinton] at the Beverly Theatre and it was frightening… 14 people singing ‘Knee Deep’ in unison. That night I went to the studio and recorded ‘Erotic City.’

O(+>

Prince’s panoply of voices on “Erotic City” carry the pungent whiff of Parliament–Funkadelic, and he was only too happy to give his heroes the credit they were due. When he inducted the legendary collective into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1997 (see above), he told a story about seeing George Clinton and the P-Funk All Stars at L.A.’s Beverly Theatre: “[I]t was frightening… 14 people singing ‘Knee Deep’ in unison. That night I went to the studio and recorded ‘Erotic City.’”8 It’s a great quote, and it appears to align with the historical record: Setlist.fm has an entry for a P-Funk show (with “Knee Deep”!) at the Beverly on March 25, 1984. But even if the precise timing was an exaggeration, Clinton’s influence is obvious in the song’s ribald, psychedelic wordplay alone; if Prince hadn’t come up with a line like “Fuck some creamy human jive,” Brother George would have had to do it for him. Which, in a way, he eventually would: recording a cover version for the 1994 college life comedy PCU that played up its P-Funk roots (in Clinton’s version, naturally, the use of “funk” as a euphemism is canon).

As was often the case, though, the artist’s acknowledgment of one “official” influence allowed other, less canonical ones to slip under the radar. More than any specific P-Funk song, “Erotic City” bears a striking resemblance to “White Horse”: a 1983 B-side by Danish synthpop duo Laid Back, the 12″ mix of which (courtesy of John Potoker and Bobby Shaw) became a runaway American club hit in early 1984. The basic ingredients were already there: thumping bass, electronic drums (in Laid Back’s case, a Roland TR-8089), and most importantly, that chirruping synth hook. All Prince had to do was add a heaping spoonful of funk, simmer, and serve hot. For that matter, I’m still not convinced the “Erotic City” hook wasn’t also a subtle dig at Twin Cities one-hit wonders Lipps, Inc.: plucking the biggest earworm from their 1980 disco banger “Funkytown” and relocating it to a sexier ZIP code. Lest you think that’s too much of a stretch, remember that Lipps’ studio guitarist and engineer was none other than David “Z” Rivkin–who Prince would soon recruit to help him remix the 12″ version of “Erotic City” in July.10 If that doesn’t sound to you like Prince’s exact level of petty, then I don’t know what to tell you.

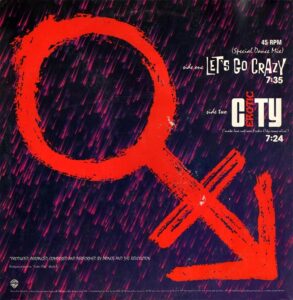

But “Erotic City” was more than the sum of its influences–whatever they may have been. When the extended mix (subtitled “Make Love Not War Erotic City Come Alive”) was released on the “Let’s Go Crazy” 12″ in late August, it quickly joined its predecessor “17 Days” in the canon of great B-sides. Exceeded it, in fact–because while “17 Days” was a perfect complement to “When Doves Cry,” “Erotic City” went further, actively making up for something its counterpart lacked. As Mike Joseph writes for Diffuser, Prince’s decision to make the B-side a funk heater as filthy as anything on 1999 served as “an olive branch” to longtime “fans who may have felt slighted by the A-side’s anthemic rock sound.”11 And while it didn’t qualify to receive its own chart placement, “Erotic City” almost certainly played the greater role in driving both sides of the single to the top of Billboard’s Dance Club chart. If nothing else, Black radio played the hell out of it: Billboard reported that “it was playlisted by approximately 25 percent of the black radio reporters, probably a much lower number than those that actually played the song. It also received airplay at a number of major-market pop stations.”12

As one might imagine, all of this mass exposure led to some controversy around the “fuck”/“funk” issue. The aforementioned Billboard report noted that the FCC fined Las Vegas radio station KLUC-FM $2,000 for playing the song in 1989, citing “at least sixteen apparent uses” of the “f-word.”13 An online repository of FCC “indecency” cases shows at least three more, dating from as late as August 1998.14 According to Wikipedia (I can’t seem to find a corroborating source), since 2004 U.S. broadcasters have played an edited version that repeats Sheila’s first half of the hook to avoid any further fines. By 2006, the song was too scandalous even for Prince, who blocked it from being released on Warner’s Ultimate Prince compilation.

On some level, this bowdlerization made sense; “Erotic City” belonged on the darkened dance floor, not the public airwaves. Its influence on underground electronic music was immediately evident: Within months of its release, it had already been interpolated (albeit crudely) by West Coast electro-hoppers the Future M.C.’s (a.k.a. Future Flash and King M.C.) on a 1984 B-side of their own, “Erotic Rapp.” Other, more artful homages would follow. But what all of Prince’s imitators lacked–aside from his razor-sharp musical acumen–was his surreal wit: An upstart producer may be able to toss together a reasonable facsimile of “Erotic City,” but not many could craft a couplet as endlessly rich as “You’re a sinner[,] I don’t care / I just want your creamy thigh.”

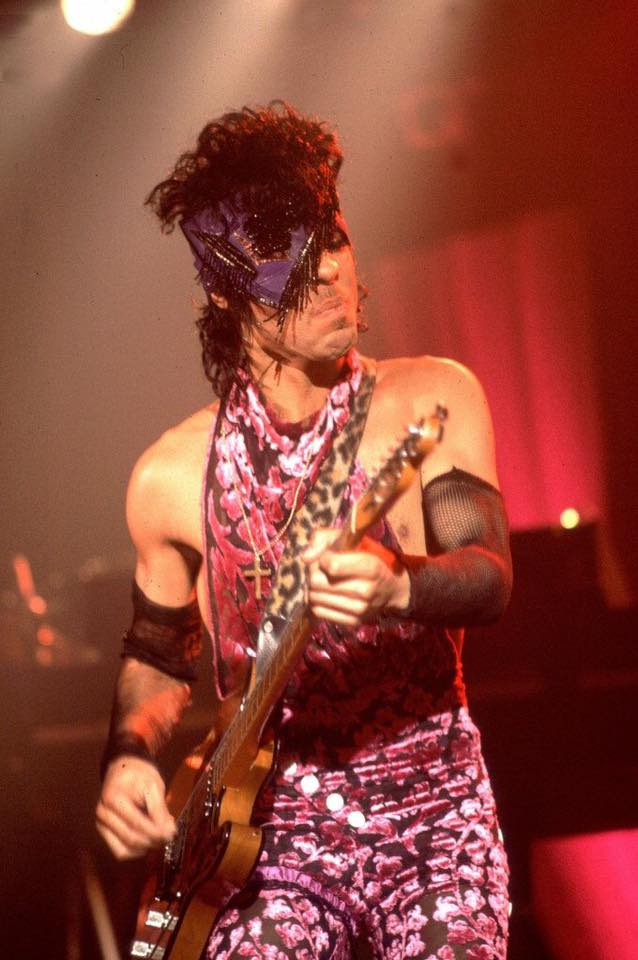

As important a milestone as it was, Prince’s own stay in “Erotic City” was surprisingly brief. He debuted the song, along with a grip of other yet-to-be-released deep cuts, at his 26th birthday show at First Avenue on June 7, 1984–over a month before the release of the “Let’s Go Crazy” single, and nearly three months before the extended version. This means that around 1,100 Minneapolitans first heard the song in mutant form, bookended by Hendrixian shredding; halfway through the eight-minute jam, a triumphal Prince smirked, “All the critics love me,” and began furiously soloing around the hook from “All the Critics Love U in New York.” On the Purple Rain tour, meanwhile, he ceded “Erotic City” to the woman he’d recorded it with: singing his part from offstage at the end of Sheila E.’s opening act, to the crowd’s audible frenzy.

Sheila, of course, was also a key player in the track’s most renowned live airing: the 1988 Lovesexy tour, where she would open the set by riding the kick drum pattern in the darkened arena while Prince drove onstage in his replica 1967 Ford Thunderbird. In keeping with the tour’s morality play structure, it’s less a conventional performance than an interpretive dance dramatizing Prince’s sexual demons. He steps out of the Thunderbird and dances with Cat Glover and Sheila in turn, leading to an altercation where Cat stage-slaps him in the face and takes Sheila by the hand instead. After a brief runthrough of the first verse and chorus, Cat and Sheila join him for a choreographed ménage à trois; one out-of-left field quote from “Sex Shooter” later, and we’re off to the races: galloping through a whirlwind tour of his most sexually-charged early songs, from “Delirious” to “Jack U Off” to an arrangement of “Sister” that verges on speed metal. In the wake of an exorcism this dramatic, it’s no surprise that he would play “Erotic City” only a few more times in the ensuing decades.

I never wanted to sing until Prince asked me to.

Sheila E.

It feels appropriate, then, to end this story in the same place where it began: the candlelit Sunset Sound Studio 3, with Prince and his latest protégée literally poised to “funk”–but not the other word–“until the dawn.” “I never wanted to sing until Prince asked me to,” Sheila later recalled. She’d sung a little on the Latin jazz-funk albums she’d recorded with her father, Pete Escovedo, in the late 1970s, but she didn’t crave the spotlight: When Lionel Richie suggested she sing the Diana Ross part of his treacly 1981 duet “Endless Love” while they were on tour together, “I said, ‘You’re crazy. I’m not going to do it.’ I get kind of scared when I hear my voice. When Prince asked me, though, I just had a feeling that he knew what he was talking about.”15

A fascinating little time anomaly (one of several that pop up around the Purple Rain era) is that by the time her first recorded vocal with Prince was released, Sheila Escovedo–the quietly ambitious percussionist Sunset Sound engineer Bill Jackson remembered hanging around the studio in “T-shirt and jeans”16–had already become “Sheila E.”: a flamboyant budding solo star with her own debut single, “The Glamorous Life,” climbing its way up the Hot 100. This metamorphosis, culminating in the album of the same title, was Prince’s next major venture as idolmaker. It would be his most ambitious to date.

(Featured Image: Roxy Twin Theatre, 42nd Street, New York City, ca. late ’80s/early ’90s; photo by Mitch O’Connell.)

Footnotes

- Sheila E. with Wendy Holden, The Beat of My Own Drum: A Memoir (Atria Books, 2015), p. 183. ↩︎

- Duane Tudahl, Prince and the Purple Rain Era Studio Sessions: 1983 and 1984 – Expanded Edition (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), p. 259. ↩︎

- E., p. 182. ↩︎

- Interview from Unsung: Sheila E. (TV One, February 27, 2012); quoted in Tudahl, p. 302. ↩︎

- Andrea Swensson, Prince and Purple Rain: 40 Years (Motorbooks International, 2024), p. 140. ↩︎

- E., p. 184. ↩︎

- Per Nilsen, Dance, Music, Sex, Romance: Prince – The First Decade (Firefly, 1999), p. 149. ↩︎

- Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, “Prince Inducts Parliament-Funkadelic into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame | 1997 Induction,” YouTube, September 10, 2012. ↩︎

- Justus Köhncke, “It’s all so tense if the clock is ticking,” Kaput, September 21, 2016. ↩︎

- Tudahl, p. 355. ↩︎

- Mike Joseph, “Prince Makes ‘Erotic City’ Come Alive: 365 Prince Songs in a Year,” Diffuser, June 5, 2017. ↩︎

- Bill Holland and Craig Rosen, “Indecency Action Sparks Radio Call for FCC Guideline,” Billboard, November 11, 1989; quoted in Michaelangelo Matos, Can’t Slow Down: How 1984 Became Pop’s Blockbuster Year (Hachette Books, 2020), p. 182. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 181. ↩︎

- College Broadcasters Resource Page, “Indecency & Obscenity: Actual cases where the FCC has acted.” ↩︎

- Tudahl, p. 302. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 223. ↩︎

Leave a Reply