In his recent cover story for Rolling Stone, reporter Brian Hiatt writes about what would become his final visit to Prince’s Paisley Park complex, in January of 2014. At one point, he describes standing in front of a mural “where a painted image of Prince, arms spread, stands astride images of his influences and artists he, in turn, influenced” (Hiatt 2016). Among the “influences” depicted in the mural are the usual suspects from Prince’s Grand Central days–Sly and the Family Stone, Tower of Power, Grand Funk Railroad–as well as Chaka Khan.

Indeed, Prince and Chaka go way back. As a teen, he’d been “a fan and a fanatic,” he told the Philadelphia Daily News in 1998. “I used to run home and see everything she was on” (Pendleton 1998). According to biographer Jon Bream, the apartment where Prince lived around the time of his signing to Warner Bros. had “45 rpm records nailed to the wall next to a poster of Chaka Khan” (Bream 1984). During the recording of his 1978 debut album For You, he would listen to records by Chaka and her group Rufus to get in the right mood for his vocal sessions; “He absolutely loved that girl,” assistant engineer Steve Fontano recalled to biographer Per Nilsen (Nilsen 1999 37). At one point, Prince even lured Chaka to the Record Plant by pretending to be Sly Stone over the phone. When she showed up, he later remembered, “I was so in awe of her I couldn’t speak, so she listened to me play for a little while, then she left” (Pendleton 1998).

I was so in awe of [Chaka] I couldn’t speak, so she listened to me play for a little while, then she left.

(The Artist Formerly Known as) Prince

Obviously, Chaka was a sex symbol; to be a Black teenager lusting after her in the mid-1970s was the rule, not the exception. But Prince’s fixation with her was much more complex and interesting than a simple crush: she was a genuine influence on his growth as a singer, as much as Carlos Santana was an influence on his growth as a guitarist. At the risk of overstating things, it’s important to acknowledge the context here. The pop music world, Black and White, has always been heavily stratified along gender lines, with unequivocally male artists firmly at the top of the hierarchy; for a heterosexual 17-year-old or 18-year-old boy to view a woman artist as a role model is, frankly, still an anomaly to this day. 40 years ago, it was evidence of an astonishingly bold artistic direction.

Prince’s 1976 recording of Rufus’ “Sweet Thing” demonstrates just how bold that direction was. He doesn’t shy away from the song’s ostensibly feminine qualities; he accentuates them. When Chaka sings “Sweet Thing” (see below), it is in its own way a subtle undermining of gender roles: her performance is strong and assured, providing the gospel-inspired “heat” and “fire” to complement her (male) band’s silky, demure musical backing. But when Prince sings it he takes on a more passive, plaintive role, the kind more typically associated with a woman: his falsetto is so delicate and fragile, one can almost imagine it blowing away like dandelions in the wind. And at the very moment in the song when Chaka’s vocals reach the peak of their power–the aforementioned “you are my heat, you are my fire” lines in the bridge–Prince just gets more vulnerable, softly harmonizing with another track of himself singing in an even higher register.

This reversal of gendered expectations would, of course, become a hallmark of Prince’s artistic persona. One of his most significant contributions to the cultural history of pop music was his inversion of the hypermasculine, hairy-chested “soulman” archetype of contemporary R&B artists like Teddy Pendergrass, presenting himself instead with a softer, more coquettish (if equally hairy-chested) seductiveness. More than any other singer before him, he made himself both subject and object of what feminist psychoanalytic theorists term the gaze, upsetting the whole gendered imbalance of power in the process. And what’s most remarkable is that he was already well on his way to doing so when he was still a kid just out of high school, recording acoustic cover songs in his friend André Anderson’s basement.

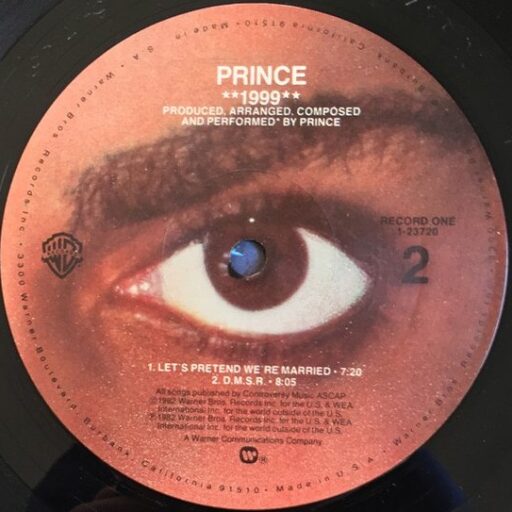

Prince’s “Sweet Thing” cover also marked the prelude to a decades-long artistic kinship with Chaka Khan. Most obviously, Chaka made his 1979 song “I Feel for You” into a massive hit in 1984–albeit with a frenetic arrangement that borrowed more from New York’s emergent freestyle scene than from Prince’s “Minneapolis Sound.” But their mutual appreciation extended much further. Prince wrote, produced, and performed on “Sticky Wicked” for Chaka’s 1988 album CK; the same record also featured a version of Prince’s “Eternity” recorded without his input. 10 years later, she signed to Prince’s NPG Records, recording another album (Come 2 My House) and joining him onstage on several occasions, including the August 28, 1998 performance at London’s Café de Paris filmed for the U.K. television special/home video release Beautiful Strange (see above). “Sweet Thing” in particular remained a staple in Prince’s live repertoire all the way up to his final months: his last known performance of the song was on February 20, 2016 at the Sydney Opera House, the fifth date of his tragically truncated Piano & a Microphone Tour.

As for Ms. Khan, she publicly commemorated Prince with the following tweet on the day of his death, including a photo of the two of them together circa 1998:

We’ll be back on Friday afternoon with another song from 1976–this one actually written by Prince.

(Thanks to Randall in the comments for reminding me of Chaka Khan’s 1988 collaboration with Prince.)

“Sweet Thing”

(Rufus featuring Chaka Khan, 1975)

Electric Fetus / Spotify / TIDAL

Leave a Reply to StephanieCancel reply