Prince’s adoption of a punk aesthetic in late 1980 and early 1981 was, as we’ve seen, an act of calculation; it would be a mistake, however, to assume that it was only that. For one thing, Prince’s New Wave songs were simply too good to have been born of strategic considerations alone. For another, as his cousin Charles Smith recalled, the artist was a known fan of “the whole English scene… He’d always been into David Bowie and that kind of stuff” (Nilsen 1999 72).

So it stands to reason that when Prince made his way to punk’s epicenter, London, in June of 1981, his P.R. approach combined thinly-veiled opportunism with genuine homage. He promoted his one-off date at the West End’s Lyceum Ballroom with a pair of high-profile magazine interviews: one with Steve Sutherland of Melody Maker, and the other with Chris Salewicz, whose tenure at NME alongside writers Tony Parsons and Julie Burchill had helped frame the discourse around British punk. Warner Bros. even took the opportunity to release a U.K.-exclusive single in advance of his visit: a distinctly New Wave-flavored outtake from the Dirty Mind sessions called “Gotta Stop (Messin’ About).”

Of the several New Wave and New Wave-adjacent songs recorded during the Dirty Mind era, “Gotta Stop” was the most transparent genre exercise–one reason, perhaps, why it didn’t make the cut for the more stylistically polyglot album. The song’s jerky, stop-start rhythm bears more than a passing resemblance to the music of Devo, whose 1980 single “Whip It” had become an unlikely crossover hit in both Black and White dance clubs. But while Devo–and most other New Wave acts–used rigid beats and jagged, nervous arrangements to express a sense of alienation and unease, Prince used them to evoke something closer to his wheelhouse: unbearable sexual tension.

Like many of his other songs from this period–“Why You Wanna Treat Me So Bad?”, “When You Were Mine,” later “Irresistible Bitch”–“Gotta Stop” is about being mistreated by a domineering, sexually experienced woman. In a canny move, however, Prince uses this stock theme to play off the New Wave genre’s studied sexlessness. As music critic Dave Hill writes, “where the New Wavers sang of sex in terms of domination and disgust, Prince invested crudity with something of the intense sexuality of which soul music is so blissfully capable” (Hill 86). Biographer Matt Thorne has described “Gotta Stop (Messin’ About)” as “censorious,” its lyrics condemning a promiscuous woman “more conservative than the louche, boundary-pushing material on Dirty Mind” (Thorne 2016). Yet even at its most deliberately robotic, the panting lustfulness with which Prince invests his performance belies his intentions. The scenario he depicts–interminably sitting outside a woman’s door while she “messes about” with other men–feels in his hands less like slut-shaming and more like the rehearsed monologue of a masochist with a cuckold fetish.

[W]here the New Wavers sang of sex in terms of domination and disgust, Prince invested crudity with something of the intense sexuality of which soul music is so blissfully capable.

Dave Hill

If we are to consider Prince a New Wave artist–and I, for one, think that we should, at least in part, and at least between the years of 1980 and 1984–then this (re-) introduction of soul and sexuality to the punk aesthetic may be his most significant contribution to the genre. Punk, especially as codified by fashion designer Vivienne Westwood and her then-partner, Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren, appropriated the signifiers of sex for shock value while almost fully divesting from its erotic meaning; bondage trousers, fishnet stockings, and dog collars were presented ironically, devoid of affect. Prince’s trick was to reappropriate that same iconography, with the erotic once again placed front and center. When he appeared on his album cover wearing what the English would call a “flasher’s mac,” he wasn’t parodying the stereotype of the pervert, in the manner of Slits frontwoman Ari Up, so much as he was simply embodying it. And when he sang about masturbating so much he was “gonna go blind,” he wasn’t (entirely) playing it for laughs, the way the Buzzcocks were with “Orgasm Addict.”

Of course, Warner didn’t release “Gotta Stop” in the U.K. because they wanted English punks to loosen up; they did it, in all likelihood, because they thought there was money to be made. “Whip It” notwithstanding, scoring an American radio hit with Prince’s new punk-influenced sound was still a longshot. The U.K. market, however, was uniquely open to post-punk and New Wave, with even the likes of the Artist Formerly Known as Johnny Rotten’s determinedly anti-music Public Image Ltd. enjoying substantial chart success. It’s easy to recognize the perceived opportunity–particularly when paired with the aforementioned press coverage and high-profile Lyceum gig introducing Prince to the English scene.

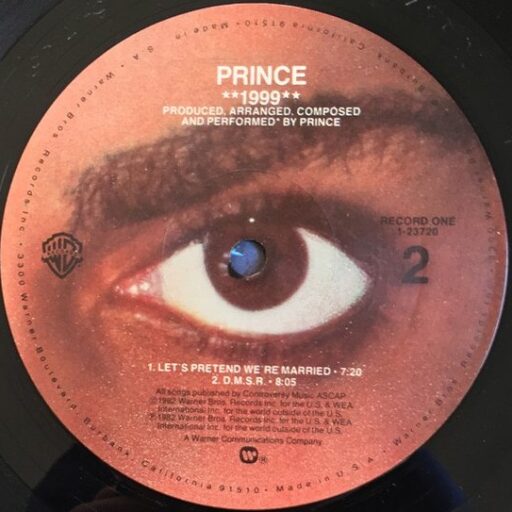

Unfortunately, this opportunity didn’t work out as planned. “Gotta Stop” was ultimately released in four separate configurations: a 7″ with “Uptown” on the B-side; a 12″ backed with “Uptown” and “Head” (affixed with a warning sticker due to the latter’s lyrical content); a second 7″ backed with, of all things, “I Wanna Be Your Lover”; and a second 12″ with both “Lover” and “Head.” None of them made the charts. Almost a year later, the track was finally given a U.S. release on the 12″ version of “Let’s Work”: the first in Prince’s storied history of non-LP B-sides. Yet even to this day, it remains at best a dark-horse favorite to an audience that tends to view Prince’s New Wave era as a passing novelty.

That’s a shame, because “Gotta Stop” is a great track–and Prince, whatever else he might have been, was also a great New Wave artist. In some alternate timeline, this could have been a standout cut by a post-punk obscurity; ironically, the song may have been buried simply because it came early in the career of a major pop star who would later rise to much greater artistic and commercial heights. Prince himself doesn’t seem to have played the song live after his brief string of European dates in the summer of 1981–though, when he did, his band gave it a muscular alternative arrangement, less Devo and more “My Sharona” by the Knack.

As for the rest of his big London premiere, the show went better than the single, if only slightly. Despite a big push from his label–including, Dave Hill reports, a giveaway of studded trenchcoats like the one from the Dirty Mind cover–Prince only managed to pack half of the Lyceum; worse, even this modest attendance had been inflated with free promotional tickets (Hill 93). Like the crowd at the Ritz the previous December, however, what they lacked in numbers they made up in influence. According to Matt Thorne, attendees included noted rock critic Barney Hoskyns, Scritti Politti frontman Green Gartside, Rough Trade Records founder Geoff Travis, comedian Lenny Henry, and infamous scenester and music journalist Paula Yates; all would, he wrote, go on to recall the show “with the same reverence that punks feel for the Sex Pistols at the 100 Club” (Thorne 2016). A contemporary review from Betty Page of Sounds magazine captured some of this notoriety in the making: in her words, “An audience who minutes earlier had been grunting, ‘Who is this bloke anyway?’ were blowing kisses, whistles, turning around and smiling at each other, knowing they were part of something special” (Nilsen 1999 76).

Prince played one more date after London, at Théâtre Le Palace in Paris, finally bringing to a close a three-month tour that had also included club dates in Royal Oak and Ypsilanti, Michigan, Atlanta, Virginia Beach, Baltimore, Boston, Cherry Hill, New Jersey, New York City, Chicago, Denver, San Francisco, West Hollywood, San Antonio, Dallas, Houston, New Orleans, and Amsterdam. He was still far from a crossover star; but he had undeniably sown the seeds for exactly the kind of dedicated cult audience he’d hoped to capture by reinventing himself as a New Waver. All that was left now was to go back to Minneapolis and turn it into a movement.

Leave a Reply