Visit the website of Pepé Music Inc. and you’ll find an entire subpage dedicated to what they call the “Prince Connection.” “We want to set the record straight!” the copy reads, and proceeds to outline the “enormous contributions” made by a man named Pepé Willie to Prince’s success: presenting its claims alongside a large and byzantine flow chart that purports to illustrate “the intimate involvement” between Willie and Prince, but, to be frank, only manages to dramatize a confusing intersection of music industry and family relationships. Yet the “Prince Connection” page also makes a trenchant point about its subject–one that will become something of a recurring theme in the early years of Prince’s musical progression. “No one,” the copy declares, “makes it completely on their own!”

Willie’s own career is a testament to that adage. He made his entrée into the music industry via his uncle, Clarence Collins, a founding member of the Brooklyn Rhythm & Blues vocal group Little Anthony and the Imperials. During his teen years in the 1960s, he worked as a valet and road manager for the Imperials in New York and Las Vegas, where he encountered the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder, and Elvis Presley; he also learned a little about the business and craft of songwriting. After a stint in the armed forces, Willie then moved out to Minneapolis in the early 1970s and married a woman named Shauntel Mandeville–who happened to be the first cousin of Prince Rogers Nelson.

His youthful brushes with fame aside, Willie wasn’t exactly a showbiz insider; when he first got to know Prince in 1974, he had just left his previous job at a “telephone company.” But, as he recently told Rolling Stone, to the kids from Grand Central and their amateur manager LaVonne Daugherty, he “was some big-time producer coming in from New York” (Grow 2016). Daugherty brought Willie on board to help develop Grand Central from a scrappy outfit winning local battles of the bands to something approaching a commercially viable group; as it turned out, he had his work cut out for him.

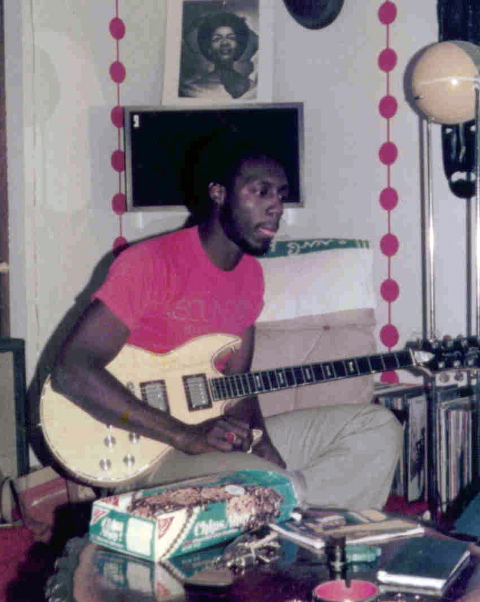

“They didn’t have any basic construction of music,” Willie recalled in 2013. “How could they go out and play cover[s] by Earth, Wind & Fire and other groups and not pick up the formula?” (Dyes 2013). The kids were skilled, but idiosyncratic in their musicianship: “Morris had a seven-piece drum set, and only played three of them,” he told biographer Dave Hill. Most vexing for Willie was the group’s tendency to jam without actually learning their parts: “I would help them out [by] getting André, Morris and the others to put down their instruments and just sing, while Prince played guitar,” he remembered. “Because, you know, one guy would be singing, ‘well, thank you’, and another would be singing, ‘well, spank you’!” (Hill 26-27)

It was during one of those undoubtedly long, arduous rehearsal sessions when Willie realized that Prince was unusually gifted, even for a precocious teen guitarist. He watched as Prince put down his guitar, took over Linda Anderson’s keyboard, and showed her the right chords to play: “I said, ‘So, he plays keyboards, huh? Alright, that’s cool.’ Then, Prince gets back on his instrument. The guys start playing again, then he stops again and said ‘[André], let me hold your bass.’ I said, ‘The guy plays bass now?’” (Dyes 2013)

None of the guitar players I’d worked with played as well as Prince for his first time in a recording studio.

Pepé Willie

Soon after that display of virtuosity, Willie invited Prince to help out with a recording session at the Cookhouse on Nicollet Avenue: the same studio, formerly known as Kay Bank, where Twin Cities garage rock classics like the Trashmen’s “Surfin’ Bird” and the Castaways’ “Liar, Liar” had been recorded. Over four hours on December 4, 1975, Prince played guitar on five compositions by Willie, later colloquially known among bootleggers as the “Cookhouse Five”: “If We Don’t,” “If You See Me,” “I’ll Always Love You,” “Games,” and “Better Than You Think.” Before the sessions, Willie had given Prince a cassette tape with demos of the songs: “I said, ‘Practice this with two leads,’ and that was it.” His cousin proceeded to play “better than a professional session player… None of the guitar players I’d worked with played as well as Prince for his first time in a recording studio” (Grow 2016).

Of the “Cookhouse Five,” the strongest was undoubtedly “If You See Me,” a breezy but melancholy soul number framed as a monologue to a former lover. “I don’t claim no riches or any miracles, but I’m doing better on my own,” Willie croons, before dipping into the chorus: “So if you see me / Walk on by, girl / Don’t say nothin’ / Walk on by, girl / Do yourself a favor.” Prince’s percussive rhythm guitar part is both soulful and technically impressive, if not immediately recognizable as the work of a man now widely considered to be one of the greatest guitarists of all time. But even then, Willie remembers, Prince’s playing had an individual flair that made him a hard man to replace: later, when Willie tried to get a full-time guitarist to replicate his cousin’s performance in concert, “it just didn’t match… It wasn’t the same sound, it wasn’t the same feel” (Dyes 2013).

Prince’s first professional recording experience revealed some tendencies that would recur throughout his career. The day after the session, Willie recalls, “Prince called my house and said, ‘Pepé, I have to go back into the studio. I made a mistake’” (Thorne 2016). No one else had heard anything wrong with the part. His perfectionism also extended to his personal behavior: he was pointedly without any of the stereotypical musician’s vices, and when the rest of the players stepped out to smoke a joint, “he’d be laughing at us because our eyes were red,” Willie told Alex Hahn. “We thought he was kind of square” (Hahn 2004 14).

Certainly, as his website argues, Pepé Willie was an important early influence on Prince: not only did he get the 17-year-old his first “real” recording session, but he also gave him some valuable pointers on songcraft, steering him away from the meandering jams that were Grand Central’s apparent stock in trade. It’s easy to imagine, too, that the future leader of the Revolution was taking notes when he saw the multiethnic, male and female makeup of the group who recorded the “Cookhouse Five,” later christened 94 East–though it’s also just as likely that both Prince and Pepé happened to be fans of Sly and the Family Stone. In any case, Willie continued to serve as a mentor for Prince in his formative years, even briefly serving as his manager after the release of his first album. But Prince was also an astonishingly quick study, and it wasn’t long before he was the one schooling his cousin.

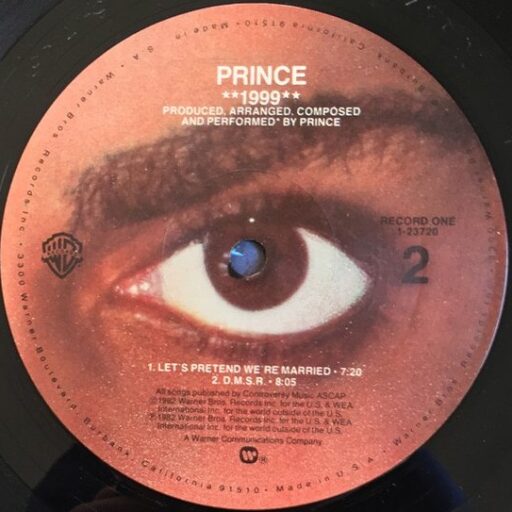

Sometime during the summer of 1982, Prince recorded a version of “If You See Me,” retitled “Do Yourself a Favor,” at his home studio on 9401 Kiowa Trail, Chanhassen, Minnesota. According to Willie, it was done entirely from memory: “He didn’t have a copy of the Cookhouse Five” (Dyes 2013). Prince’s version blows the original out of the water. His new arrangement gives the song a brisk New Wave cast, with a galloping surf rock beat and sprightly synthesizer pattern; his guitar part is less traditionally funky, but infinitely more melodic and hooky, adding a brief, talkbox-enhanced solo and some soulful, Curtis Mayfield-esque embellishments. Most notably, his vocal performance draws the emotion out of Willie’s rather flat, expressionless melody; and, as the title change suggests, he tweaks the song’s hook to great effect, hanging the chorus on its more dynamic turnaround, “Do yourself a favor,” rather than the more conventional “If you see me / Walk on by.” Finally, after about four minutes, he launches into an extended vamp nearly as long as the actual song, slipping into the camp “pimp” voice he gave to Morris Day and the Time and making the whole thing seem like an elaborate joke: “Somebody call up the Colonel, I hear some chicken scratchin’,” he rasps hilariously over the breakdown.

Willie remembers Prince tracking him down and playing him his version of “Do Yourself a Favor” sometime in the early ’80s; he’d supposedly promised to put it on an album, but like so many other perfectly good Prince songs, it remained consigned to the infamous “Vault” until it was liberated by an enterprising bootlegger, before finally receiving an official release on the 1999 Super Deluxe box set. The song did eventually get its day in the sun when former Time guitarist Jesse Johnson covered it for his 1986 album Shockadelica. Johnson’s version is credited to Willie, who got a cut of the publishing; listen to the arrangement, however, and it’s clearly more indebted to the Prince take.

Which, I suppose, is the moral of this story in the end. Yes, no one makes it completely on their own; but give the right person the right material, and they might just transform it into something beyond what anyone thought they were capable of. And by 1982, like the song says, Prince was “doing better on his own.”

(This post was edited to include a link to the officially released 1982 version of Prince’s “Do Yourself a Favor.”)

“If You See Me”

(94 East featuring Prince, 1975)

Electric Fetus / Spotify / TIDAL

“Do Yourself a Favor”

(Prince, 1982)

Spotify / TIDAL

“Do Yourself a Favor”

(Jesse Johnson, 1986)

Electric Fetus / Spotify / TIDAL

Leave a Reply