Shortly after coaxing her into recording her first pop vocal on “Erotic City,” Prince had another proposition for his new right-hand woman, Sheila Escovedo. “One day at Sunset Sound he turned and asked me, ‘So, do you want to make your own record?’” she recalls in her 2014 memoir The Beat of My Own Drum. “I laughed and said, ‘It’s that easy, right?’”1

For Prince, it kind of was. On Wednesday, March 28, 1984, he had engineer Peggy McCreary compile six recent tracks on cassette for himself, Sheila, and Warner Bros.–the exact same songs that would comprise her debut album when it was rushed to market an astonishing 68 days later. On the work order was a new, streamlined name for Escovedo: “Sheila E.”2

One day at Sunset Sound [Prince] turned and asked me, ‘So, do you want to make your own record?’ …I laughed and said, ‘It’s that easy, right?’

Sheila E.

Given Prince’s reputation as a serial stage-namer, it would be tempting to assume that he was the mind behind this rebrand. In fact, like the similarly-monikered Bobby and David Z, it originated from a childhood nickname: “Escovedo had never been an easy name to say or spell,” Sheila writes. “Since middle school, people referred to my brother Juan as Juan E. And soon I was Sheila E.” When she suggested it to the maestro as her new nom de Prince, “he said that [it] was perfect and far more commercial than anything he could think of.”3 All that was left was to sign with Cavallo, Ruffalo, and Fargnoli, which she did without “read[ing] the small print”–a decision she, like many a Prince protégé both before and after her, would come to regret.4

With Sheila now officially part of the Starr ★ Company stable, she and Prince proceeded to complete the album in a flurry of activity: “we’d stay up until five and six in the morning recording, go home for a couple of hours, come back and start playing again,” she told Billboard in 2016. “Next thing you know, seven days later, the record’s done.”5 In her version of events, “the last song [they] worked on” was the album’s eventual title track.6 This, however, doesn’t match the historical record: Of the songs Prince selected for the project, “The Glamorous Life” was actually recorded earliest, on December 27, 1983.

That evening, writes sessionographer Duane Tudahl, Prince “quickly started laying down a melody in E-flat minor, using only the black keys on the piano.”7 With this infectious hook as his base, he added a stuttering Linn LM-1 pattern and layers of Oberheim OB-8 synthesizer–but he wanted to go beyond these standard accoutrements. A few months earlier, he’d made an abortive attempt at recording his own saxophone part for “G-Spot”; this time, though, he knew the sound in his head required a professional to realize. So assistant engineer Terry Christian called in Larry Williams: a multi-instrumentalist (not to be confused with either the singer of ’50s rock and roll hits like “Bony Moronie” or the photographer responsible for much of Prince’s Purple Rain-era imagery) best known for his work with the 1970s fusion band Seawind and his credits on recordings by George Benson, Michael Jackson, Al Jarreau, the Brothers Johnson, Quincy Jones, Rufus, and many others.

[Prince] wanted it to sound [like] more of a street sound, less slick. I’m used to coming in to an R&B situation and I’m [the one] trying to sneak some hip stuff in, something unusual.

Larry Williams

When Williams arrived at Sunset Sound’s Studio 3, he was met by Prince in his best Louis & Vaughn finery: “this velvet shirt with ruffles and some kind of hat. To me it was really ridiculous,” he admitted. As was often the case with studio players, however, the more time he spent with the artist, the more his initial bemusement gave way to professional esteem: “it was incredible how focused he was on the music and how there was just no bullshit of any kind.” He laid down a number of alto sax parts for Prince to disperse through the track–including a triad of brash, bebop-inspired solos that spice up the beginning, midpoint, and end of the album edit. According to Williams, it was Prince’s idea for him to play something “free and bizarre”: “He wanted it to sound [like] more of a street sound, less slick. I’m used to coming in to an R&B situation and I’m [the one] trying to sneak some hip stuff in, something unusual.”8

As Tudahl notes, this hint of hard jazz wasn’t entirely out of step with the contemporary pop scene: The album version of David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance,” released about eight months prior to the recording of “Glamorous,” features similarly “hip” solos by trumpeter Mac “Chops” Gollehon and saxophonists Robert Aaron, Stan Harrison, and Steve Elson.9 But it wasn’t mere trend chasing, either. Over the next year or so, saxophone would play a growing role in Prince’s sound, culminating in Eric Leeds joining the expanded Revolution for the final leg of the Purple Rain tour in February 1985.

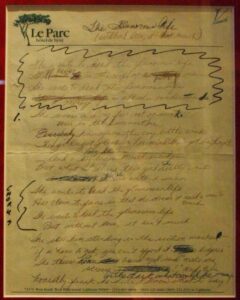

Having finished the basic track with a little help from Williams and his horn, Prince returned the following day with lyrics, “written out on several pages of stationery from Le Parc Hotel in West Hollywood,” where either he or a consort was presumably staying.10 If his Purple Rain leading lady Apollonia is to be believed, that consort just might have been her: In a now-deleted interview with podcaster Drew Dempsey, she claimed to have had a hand in writing the song. Based on her similar, but more substantiated assertions about “Manic Monday,” she probably meant that she contributed a few lines–though as far as I can tell, the only handwriting on the lyrics sheet (see right) is Prince’s own. Perhaps the safer bet is to credit her for more nebulous “inspiration”: In 1994, she told Per Nilsen’s Uptown fanzine that the song “was written by Prince as a joke to me. He used to make all these stupid jokes, [like] ‘You’re the kind of chick who would wear a mink coat in the summertime.’”11

Whether inspired by Apollonia specifically or (more likely) a composite of women both real and imagined, the unnamed protagonist of “Glamorous” cuts a similar figure to many in Prince’s growing gallery of femmes fatale. She’s alluring and well heeled: not just the “kind of chick” who “wears a long fur coat of mink / Even in the summer time,” but also the kind who shops for lingerie in “the section marked / ‘If you have to ask, you can’t afford it.’” She’s also sexually aggressive: When she spots a prospective conquest in the aforementioned intimates department, her approach is to throw him a wad of cash and demand, “make me scream.” Moments later, they’re speeding in her “big brown Mercedes sedan” to her lair at “55 Secret Street”–the same part of (Up)town, no doubt, where Darling Nikki and the Little Red Corvette live.

What sets this maneater apart from her elder sisters is a more pronounced sense of vulnerability, achieved in part through a shift in narrative viewpoint. Both “Nikki” and “Corvette” are grounded in the first-person perspective of Prince’s wide-eyed seducee, their subjects as ultimately unknowable as they are irresistible. But “Glamorous” uses a third-person limited point of view: keeping its protagonist at a discreet remove, while offering the occasional glimpse into her inner thoughts. It’s an effective choice–never more so than in the narrative climax, when our heroine realizes she’s met her match after reaching her own climax (or seven) with the help of her lingerie-shopping mystery man.

Prince took away the song… and gave it to [Sheila]. At that point I was like, ‘Man, this is just not fair.’

Apollonia

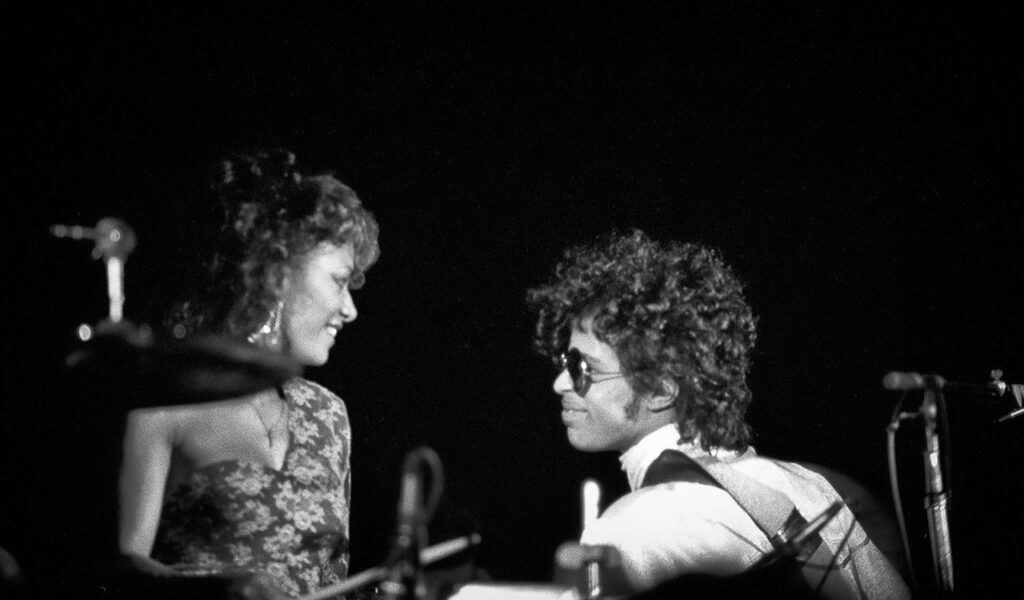

Prince recorded a guide vocal for “Glamorous” that would eventually see release on 2019’s Originals compilation, but the song was obviously intended for a female singer. With a man in the narrator’s role, the central character study threatens to come across as smug and condescending, not to say a tad sexist: An ice queen with the temerity to believe she “don’t need a man’s touch,” getting her comeuppance via lifechanging dick. It needs, ironically, a woman’s touch–or more accurately, the touch of someone who has known the indignity of loving straight men–to bring the right blend of imperiousness and sensitivity to lines like, “Boys with small talk and small minds / Really don’t impress me in bed.” The question was, which woman? Apollonia, by most accounts, was the early favorite: She even dropped by Sunset on December 28 to hear Prince’s progress on the track–the strongest evidence, in my mind, for her claim of inspiring it. Another contender was Jill Jones, who added backing vocals later that same evening, and whose own Prince-produced album was supposedly still in the works.12 The studio work orders, though, all listed Prince as sole artist–both for the initial recording sessions and on January 6, when he had David Coleman record a cello part to bolster the main hook.13

In the end, of course, the song would belong to Sheila, pretty much from the moment she added percussion on February 8. Her contributions transform the track from the ground up, with a propulsive cowbell beat, explosive timbale fills, and a solo and extended coda that finds her weaving nimbly between Prince’s synths and Williams’ saxophone. Listen to the version on Originals, which most closely resembles the basic track as it was in January, then chase it immediately with Sheila’s album version; the difference is as clear as night from day. Intriguingly, the session where she recorded her overdubs was the song’s first to be booked with Apollonia 6 listed as the artist; but by the end of the night, writes Tudahl, the group’s name had been crossed out and replaced once again by Prince’s.14 Two weeks later, he requested a safety copy of recent songs that specifically named Sheila as artist–a clear indication that his plans for her were rather less spontaneous than she’s made them seem.15

This changing of the guards went over about as well with the song’s original beneficiaries as you’d expect. “When Sheila came into the scene, Prince took away the song from us and gave it to her,” Apollonia recalled. “At that point I was like, ‘Man, this is just not fair.’ Since I was a newcomer, I kinda bit my tongue, but Susan and Brenda really let him have it.”16 Jill, typically, minced even fewer words: “I was really a little bit pissed off,” she told Tudahl, “because Sheila was just showing up at the studio in her basketball-looking clothes and whatever… And then my project got kicked backwards because of Sheila.”17

Such reactions may sound petty in retrospect, but they also make sense; Prince, Sheila, and the other girls all knew what they had. “Glamorous” would give Sheila’s debut album not only its title, but also its lead single: the first shot across the bow, indeed, in the whole Purple Rain promotional blitz, beating even “When Doves Cry” to the racks by two weeks. Like “Doves,” its gradual ascent up the charts–peaking at Number 7 on the Billboard Hot 100 that October–was assisted by its music video, which featured Sheila flaunting both her percussion chops and her aptly ’80s-glamorous new look. The latter came courtesy of Louis & Vaughn, who had her trade in her “basketball-looking clothes” for a bespoke satin and leopard-print pantsuit and bustier in the performance shots, as well as the inevitable “long fur coat of mink” in the narrative sequences. She also sported a new perm by Prince’s hairdresser in residence, Earl Jones–a connection that particularly stuck in the craw of his niece, Jill.18

Prince clearly saw in Sheila a budding star with mainstream commercial appeal, and “Glamorous”–its video in particular–was him going all in on that potential. His team hired Mary Lambert, an up-and-coming director who had attended the Rhode Island School of Design with Talking Heads’ Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth, and whose debut video for Madonna’s “Borderline” had just made a big splash on MTV. (Later that same year, of course, Lambert and Madonna would make an even bigger splash with “Like a Virgin”; and, as anyone reading this presumably knows, she’d briefly helm Prince’s second feature film, Under the Cherry Moon, before being summarily replaced by its star.) The “Glamorous” video finds the young director reaching into the same bag of tricks that had served “Borderline” so well: blending black-and-white and color footage–an artistic choice, Lambert recalled, that had made Madonna’s management “hysterical”19–and juxtaposing gritty contemporary cityscapes with touches of Old World romance (compare the classical marble sculptures that adorn the photographer’s studio in “Borderline” with the Venetian Carnival-inspired revelers who parade through the downtown L.A. streets in “Glamorous”).

One trick Lambert wasn’t allowed to repeat from her previous hit, however, was its portrayal of an interracial romance. At Madonna’s behest, the “Borderline” video had dramatized her character’s “affair with a cute Hispanic boy who was part of the street scene.”20 Along similar lines, recalled producer Sharon Oreck, she and Lambert “hired a really handsome black guy to play Sheila E.’s love interest” in “Glamorous.” “A short while later, we heard from Simon Fields [of production company Limelight] that Prince’s camp didn’t like him… Mary Lambert said, ‘Why don’t they like him? Is he too tall? Too short?’ And finally Simon said, ‘They don’t want a black guy.’ …We were told they wanted the record to cross over, so there needed to be a white boyfriend.”21

[W]e hired a really handsome black guy to play Sheila E.’s love interest. A short while later, we heard from Simon Fields that Prince’s camp didn’t like him… We were told they wanted the record to cross over, so there needed to be a white boyfriend.

Sharon Oreck

It feels unlikely, to say the least, that this cold-blooded directive would have come from Prince himself; yet Oreck’s story makes it clear how much his team was banking on “Glamorous” to be a breakout pop hit. Still–and even taking into account MTV’s problematic history with race–it’s hard not to conclude that they were overthinking things. Black or White, the male lead is arguably the least remarkable part of the video; when fans think back to it today, they’re far likelier to remember Sheila herself, leading her band from center stage and ending her timbale solo with an iconic high kick to the splash cymbal. They’re likelier still to recall her performance at the 1985 American Music Awards–the same night Prince and the Revolution brought the house down with “Purple Rain”–where she repeated the cymbal-kicking stunt and played the climactic solo with the aid of glow-in-the-dark drumsticks (see video above).

Moments like these were the real reason why “The Glamorous Life” went to Sheila—and why, frankly, it wouldn’t have been anywhere near as big a hit for Apollonia (or Jill, for that matter). Prince had tried before with his protégées, most notably Vanity, to Pygmalion a female version of himself; but while a few of these femme-Princes (Princesses?) could emulate him as a sex symbol, none before Sheila had the stage presence or musicianship. “I don’t believe he ever had a woman around him before who could hang like I did,” she writes in her memoir. “I mean musically, athletically, creatively, and competitively.”22 And if that comes across as self-aggrandizing, well, where’s the lie?

I don’t believe [Prince] ever had a woman around him before who could hang like I did. I mean musically, athletically, creatively, and competitively.

Sheila E.

Sheila has a tendency to exaggerate her role in the creation of her music with Prince–an effort, one assumes, to further distance herself from the “Prince protégée” stereotype. She claims, for instance, that before she recorded her vocals for “Glamorous,” the song was “an instrumental,” and that the lyrics were hers.23 This, again, does not appear to be the case; it’s also an unnecessary fabrication. She may not have written the song, but she did make it her own, on stages around the world–with Prince; with her own band; with Ringo Starr’s All-Starr Band; even on a Royal Caribbean Cruise that shared its name.

In a larger sense, Sheila and “The Glamorous Life” also signaled a sea change in Prince’s sound–not just through the previously-noted introduction of live horns, but also by setting a new standard of musicianship in general. The “band” backing Sheila in the “Glamorous” video had been a makeshift assortment of friends and family members, including her sister Zina and brothers Juan and Peter Michael–many pretending to play instruments they didn’t actually play, or that weren’t on the original recording.24 When it came time to prepare for her role as opening act on the Purple Rain tour, she went back home to Oakland to recruit a proper band, including Juan (now on real percussion, rather than mimed keyboards), guitarists Stephan “Stef Burns” Birnbaum and Michael “Miko” Weaver, keyboardist Susie Davis, saxophonist Eddie “M.” Mininfield, drummer Karl Perazzo, and bassist Benny Rietveld. When Prince flew out to observe one of their rehearsals over the summer, she writes, he “called his tour manager to arrange an emergency meeting with the Revolution” back in Minneapolis. “When he got home four hours later, he apparently told them he was changing the entire show. ‘Ain’t no way Sheila’s gonna have a funkier band than me!’ I heard he told them.”25

This story may or may not be literally true, but the idea it expresses is surely genuine. Both before and during the Purple Rain tour, Prince would use members of Sheila’s band to augment his own Revolution at rehearsals, soundchecks, and encores; they even appear on the 12″ extended version of “I Would Die 4 U,” captured at an October 1984 tour rehearsal at the Minneapolis Auditorium. By the Parade tour in 1986, he’d drafted Miko into the band as an auxiliary guitarist. And of course, when he finally deemed the Revolution no longer fit for purpose, it was Sheila and her Bay Area compatriots who would form the core of his band for the Sign “O” the Times and Lovesexy tours. Sheila, in other words, was more than just a new breed of side project for Prince; she was a key driver behind the next stage of his musical development, months before most of the world had caught up to where he already was. As Prince would quip during the 1987 Sign “O” the Times shows, “Not bad, for a girl.”

(Featured Image: Warner Bros. publicity shot of Sheila E. by Larry Williams–again, no relation to the sax player–used for The Glamorous Life album and single art; stolen from Lansure’s Music Paraphernalia.)

Footnotes

- Sheila E. with Wendy Holden, The Beat of My Own Drum: A Memoir (Atria Books, 2015), p. 188. ↩︎

- Duane Tudahl, Prince and the Purple Rain Era Studio Sessions: 1983 and 1984 – Expanded Edition (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), p. 305. ↩︎

- E., p. 189. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 188. ↩︎

- Jem Aswad, “Sheila E. Looks Back on Prince: Their Collaborations, Engagement & Lifelong Love,” Billboard, April 26, 2016. ↩︎

- E., p. 190. ↩︎

- Tudahl, p. 199. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 200. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 201. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 202. ↩︎

- Per Nilsen, “Let Me Guide U 2 the Purple Rain,” Uptown No. 14 (July-September 1994); quoted in Benoît Clerc, Prince: All the Songs – The Story Behind Every Track (Mitchell Beazley, 2022), p. 582. ↩︎

- Tudahl, p. 202. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 218. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 260. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 274. ↩︎

- Nilsen, quoted in Clerc, p. 582. ↩︎

- Tudahl, p. 261. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Craig Marks and Rob Tannenbaum, I Want My MTV: The Uncensored Story of the Music Video Revolution (Dutton, 2011), p. 193. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 215. ↩︎

- E., p. 189. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 190. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 194. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 213. ↩︎

Leave a Reply