On March 18, 1984–the day after he exhumed and reburied “Possessed”–Prince turned his attention to another track previously attempted during the prolific August 1983 rehearsals at the St. Louis Park Warehouse. According to keyboardist Lisa Coleman, the seed of “17 Days” had been planted when she improvised a reggae-style riff on the organ, and “we just started jamming on that.”1 “I remember all of us coming up with our own parts on it,” recalled the group’s other keyboardist, Dr. Fink.2 Prince’s main contribution was the melody–what Coleman referred to as the “‘ha ha ha’ backing vocals” of the chorus. “I think he had the lyrics the next day.”3

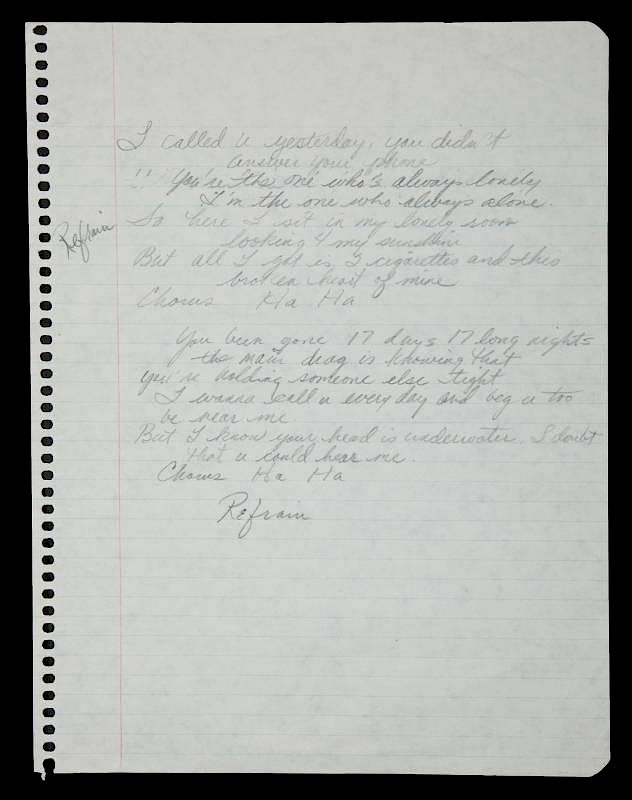

The lyrics he came up with were pure blues, of a piece with songs like “Gotta Broken Heart Again” and “How Come U Don’t Call Me Anymore?” Like the latter track in particular, “17 Days” opens on our protagonist being ghosted by a fickle lover: “Called you yesterday,” he sings, “you didn’t answer your phone / The main drag is knowing that you probably weren’t alone / So here I sit in my lonely room, lookin’ for my sunshine / But all I got is two cigarettes and this broken heart of mine.” The premise is familiar territory for Prince, who as Coleman noted, “sang the part of the lonely person a lot.”4 But what it lacks in novelty, it makes up in its accumulation of poetic details: the “two cigarettes” and accompanying double meaning of “main drag”; the chorus’ prayer to “let the rain come down,” at once evoking baptism and Biblical flood; even the “17 days and 17 long nights” his lover has been away, a length of time so specific it acquires its own weight of meaning. Part of this meaning is, again, scriptural: In Genesis, the flood begins on “the 17th day of the second month” in Noah’s 600th year. But there’s also just “something very poignant about counting the hours and counting the days,” explained Vernon Reid of funk metal pioneers Living Colour, who would cover the song for the B-side of their 1993 single “Ausländer.” “That’s the beauty of it–it’s not 18 days, it’s not 19 days.”5

There’s something very poignant about counting the hours and counting the days. That’s the beauty of it–it’s not 18 days, it’s not 19 days.

Vernon Reid

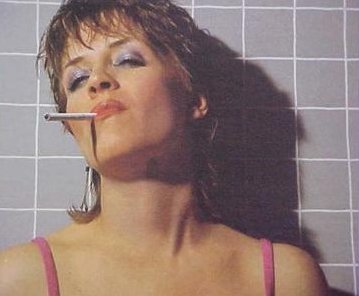

Another detail–the line about cigarettes–put some distance between “17 Days” and the established Prince persona, which was seldom associated with tobacco use. In fact, Prince seems to have initially written the song as a vehicle for Brenda Bennett of the group soon to be formerly known as Vanity 6, whose own onstage “character” was rarely depicted without a coffin nail dangling from her fingers or lips. “We rehearsed it with the band at the warehouse with Brenda singing lead,” engineer Susan Rogers told Uptown magazine. Her account is corroborated by Brenda’s then-husband Roy Bennett, who remembered, “I was back home in Rhode Island and she called me, and was all excited about a new song that she’d recorded with Prince, ‘17 Days.’”6 Brenda’s lead vocals even seem to have made it onto at least one recording: In a 2014 interview, she dropped the tantalizing detail that she still had the tape from “when I did the song for the second Vanity 6 album.”7

Of course, that album would never come to be: Less than a month later, Vanity would walk away from the Purple Rain project and her namesake group alike. But Prince kept “17 Days” close. It remained a staple of his jams with the band soon to be officially dubbed the Revolution: Sessionographer Duane Tudahl describes an especially intriguing session, captured at Sunset Sound on September 18, 1983, which featured Prince on bass, Lisa on keyboards, Wendy Melvoin on guitar, and the Time’s Morris Day on drums. Picking up again on Lisa’s reggae-inspired organ part, Prince worked in interpolations of the 1979 single “Down in Jamaica” by roots reggae band Culture and the lovers rock homage “Do You Really Want to Hurt Me” by London New Wavers Culture Club (no relation). Then it was back to his old bag of tricks: Switching to his “Jamie Starr” voice, he “called for the track to be faster, funkier, and nasty,” dropping in elements from the Time’s “Cool” and “Chocolate,” the ever-reliable “Cloreen Bacon Skin,” and the yet-to-be-recorded “Cold Coffee & Cocaine,” with “Cold Sweat” providing the obligatory James Brown riff.8 “There was no title for this workout,” Tudahl writes, “but Prince tried to include the phrase ‘If I had my way baby, I’d put you in the hall of fame.’”9

[Prince] acquired a more fearless approach… when he started out in a session with spiritual and gospel playing.

Jill Jones

This “studio jam” version of “17 Days” still hasn’t seen the light of day, either officially or (to my knowledge) in most bootleg-trading circles; but the next phase in the song’s evolution would circulate for decades, before finally receiving an official release on 2018’s Piano & A Microphone 1983. The 35-minute home recording, dating most likely from October of the titular year, captures Prince alone at his Yamaha CP-70 electric grand, working through a free-associative blend of recent compositions, covers, and apparent improvisations, including the aforementioned “Cold Coffee & Cocaine” and the embryonic “When Doves Cry” progenitor “Why the Butterflies.” In what feels like a clue to the song’s prominent place in his subconscious, the rehearsal kicks off with “17 Days”; yet the version captured here is a far cry from the vaguely reggae-flavored jam described by Coleman and Tudahl. Instead, as Coleman writes in her liner notes for the deluxe edition of Piano & A Microphone, “here Prince is getting closer” to the song, “getting it in his body.”10

Appropriately for a set that also includes the Spiritual “Mary Don’t You Weep,” Prince’s means of getting “17 Days” “in his body” was to tap directly into the mainline of Black musical tradition. He launches into a bluesy, minor-key groove, stomping on the floor to keep time. Without missing a beat, he asks engineer Don Batts to “turn the lights down.” His request presumably granted, he leans into the microphone and rasps, “Good God!” in a voice that channels James Brown by way of Jamie Starr. He rides the groove for a few more bars, beatboxing the bassline, then cuts loose with a pair of convulsive micro-solos. The performance evokes singer Jill Jones’ description of how he’d “sometimes play spiritual tunes and impersonate how his dad would play them[:] With all of these rumblings and grumbling assaults on the keyboard yet an intrinsic exploration, knowledge and usage of every key to be played and its capabilities.” Prince, Jones writes, “acquired a more fearless approach… when he started out in a session with spiritual and gospel playing.”11

In this raw musical setting, the lyrics acquire a new intimacy, their origins in the blues shining through. After singing the two verses and refrain–with a short break for another piano solo–Prince returns to the second verse, code-switching to a more vernacular register: “The main drag is knowing that / You’re holding someone else tight” becomes, “Oh, it’s a drag, baby, and I know / [You’re h]oldin’ another n**** tight.” His use of that most charged of racial epithets–a relative rarity in his recorded work to this point–further roots the performance in a sense of history, recalling the in-group ad-libs with which he would pepper his shows in majority-Black cities like Detroit (e.g., “when I saw all the pictures of the Negroes / That were there before me”). As if to cement these connections, he closes the final refrain with some vocalizing straight out of the Black church; then he hums the ghost bassline again, tosses in a few stray lyrics from “The Bird,” and ends the groove as abruptly as it began, shifting gears into the languid opening notes of “Purple Rain.”

[Prince] just wanted the right vibe. Maybe if he had taken more time to be a little ‘hi-fi,’ he might have lost the edge.

Bill Jackson

He would pick up the groove again a few months later–either late December or early January, by Tudahl’s reckoning–when he, drummer Bobby Z, Lisa and Wendy, and their respective siblings David Coleman and Jonathan Melvoin, arrived at Sunset Sound to cut the master version. By this point, Prince had been jamming on “17 Days” for so long that he wanted plenty of room to stretch out; so he instructed assistant engineer Bill Jackson to roll the tape at a slower speed (15 ips, or inches per second, rather than the then-industry standard 30), allowing for more recording time at a cost to fidelity. “I said[,] ‘That’s not aligned. It’s not going to sound right,’” Jackson remembered, “but he didn’t care about that and said, ‘Just do it.’” The ever-mercurial artist then proceeded to launch into the song before Jackson was ready, leaving the soundman scrambling: “As they were playing I was adding some EQ and making things sound a little better and getting the levels right and they played until the tape ran out for like thirty minutes.”12

Far from being to the song’s detriment, however, these apparent imperfections are critical to its magic. The lower noise floor and wider dynamic range of a 30 ips recording may have sounded better to the ears of a professional engineer in the high-fidelity 1980s, but 15 ips is increasingly valued for imparting a warmer, more ’60s or ’70s sound–a perfect fit, in other words, for the psychedelic territory Prince’s music was increasingly inhabiting. The slower tape speed is also prized by audiophiles for its superior low frequencies: an area where “17 Days,” with its infectious bassline and bottom-heavy beat, clearly excels. In the end, even Jackson had to admit that his client was onto something: “He just wanted the right vibe,” he told Tudahl. “Maybe if he had taken more time to be a little ‘hi-fi,’ he might have lost the edge.”13

As for the reason he’d insisted on 15 ips in the first place, Prince took the half hour or so he’d captured on tape, chiseled it down to seven minutes and 22 seconds, and spent the next few hours on overdubs. The result is an abundance of aural pleasures. He opens the track with a circular, finger-tapped bass riff, his Boss BF-2 Flanger creating a vertiginous, swirling effect. A few measures later and the drums break in like a thunderclap, while Prince’s bass takes up the same loping line he’d hummed over his piano that past fall. At last, the clouds part: A keyboard glissando cuts through the murk, making way for rhythm guitar, tambourine, and a lustrous lead synth line. If the solo piano version was stark monochrome, then the studio take is vivid Technicolor; yet it remains true to its melancholy core. It’s a prime example of what writer Hanif Abdurraqib dubbed the “sad banger”: a song “whose lyrics of grief, anxiety, yearning or some other mild or great darkness are washed over with an upbeat tune, or a chorus so infectious that it can weave its way into your brain without your brain taking stock of whatever emotional damage it carries with it.”14

With its sun-dappled sonic palette and relatively organic instrumentation, “17 Days” also shares a vibe with some of the songs Prince was considering for the Apollonia 6 album–particularly “Take Me with U” and “A Million Miles.” Certainly, Brenda is all over it: her backing vocals on the aforementioned “ha ha ha” chorus ring through like a bell. Toward the end of the seven-minute version that circulates among collectors, she gets an even bigger opportunity to shine, putting on her best dispassionate fembot voice to recite one of Prince’s patented psychosexual soliloquies: “No more will I accept your majestic macho attitude toward my womanhood / Yes, I can see the fact that you are beautiful / But my dear, so am I / When will I be able to cut through the celluloid surface that surrounds your world and make you see this / As well as you can see my vagina?” Her conspicuousness in the mix–not to mention the, ahem, explicitly female perspective of the monologue–suggests that Prince still intended the song for her, either as part of the group or for a potential solo project.

By the time he returned to the track in March, though, plans had clearly changed. “17 Days” became the first of many songs Prince would take back from the ill-starred trio: a list that would also grow to include the aforementioned “Take Me with U,” “Manic Monday,” and two-thirds of Sheila E.’s The Glamorous Life. “I think the reason why ’17 Days’ didn’t go to the girls was just because he felt it was too good for them,” Roy Bennett later surmised. “He didn’t want to waste it on something, that’s terrible to say, but on something he didn’t feel was going to sell as much as that song could have sold.”15 It didn’t hurt that, with “Doves” now on deck for his next single, Prince was in the market for a suitably killer B-side–a role “17 Days” would fill with aplomb. Indeed, squint a little and the two songs start to look like halves of a complementary whole: Both juxtapose rich, emotionally complex lyrics with danceable beats and chirpy, pastel-tinged hooks; but where “Doves” is a product of solo studio mastery, “17 Days” is the sound of a group of musicians playing off each other in real time. Even the ample bass feels like a missing link, making up for the A-side’s notorious lack thereof.

I think the reason why ’17 Days’ didn’t go to the girls was just because [Prince] felt it was too good for them.

Roy Bennett

Having reclaimed the track, Prince spent much of March 18 and 21 polishing it to a gleam: adding overdubs–including auxiliary percussion by his new secret weapon, Sheila Escovedo, and additional backing vocals by his old one, Jill Jones–and trimming nearly three and a half minutes from the runtime. The most notable casualty was Brenda’s “vagina” monologue—a disappointing choice, if perhaps an understandable one, for “Weird Prince” connoisseurs everywhere. Yet even in truncated form, “17 Days” retained its sense of enigmatic verbosity: in its copyright filing and on the “Doves” B-side, it came saddled with the endearingly portentous subtitle, “the rain will come down, then U will have 2 choose. If U believe, look 2 the dawn and U will never lose.”

This invocation of “the dawn”–a concept of growing significance in Prince’s personal cosmology–feels like yet another indication that “17 Days” was one of his personal favorites. It wouldn’t be the last. Back in Minneapolis in early April, he reportedly slipped a tape to the DJ at First Avenue to play for the crowd weeks before its official release. Later, it joined “Possessed” in his setlist for the Minnesota Music Awards in Bloomington on May 21, as well as his 26th birthday show back at First Avenue on June 7. It remained a staple of Revolution rehearsals and soundchecks. In these performances, the arrangement mutated again: building on the extended jam elements the single edit had left on the cutting room floor, with Lisa’s organ vamp and Brown Mark’s percussive bassline taking the lead. The Parade tour in 1986 took advantage of the expanded Revolution lineup, giving the lead line to horn players Eric Leeds and Atlanta Bliss and sneaking in a riff from “I Wanna Be Your Lover.”

By its 20th anniversary in 2004, “17 Days” had become nearly as beloved by fans as its more famous A-side–maybe even more so. Prince acknowledged as much when he included a snippet in a segue on Musicology, with a simulated radio dial tuning past the song alongside heavy hitters “If I Was Your Girlfriend,” “Kiss,” “Sign ‘O’ the Times,” and “Little Red Corvette.” Seven years later, it had officially entered the canon: another familiar favorite for Prince to sprinkle into the setlists of his various “Welcome 2” tours. There’s a great version on the Blu-ray from 2021’s deluxe Welcome 2 America release (see above) that fits in a tribute to the late Teena Marie, pairing the lead line with the similar descending melody from her 1984 single “Lovergirl.”

As for the woman from whom “17 Days” got away, Brenda Bennett would finally got her turn in the spotlight when she covered the song on her 2017 solo album Once Again. It’s a fine version, but don’t get too excited, Weird Prince fans: she didn’t do the speech. Some things the world may never be ready for.

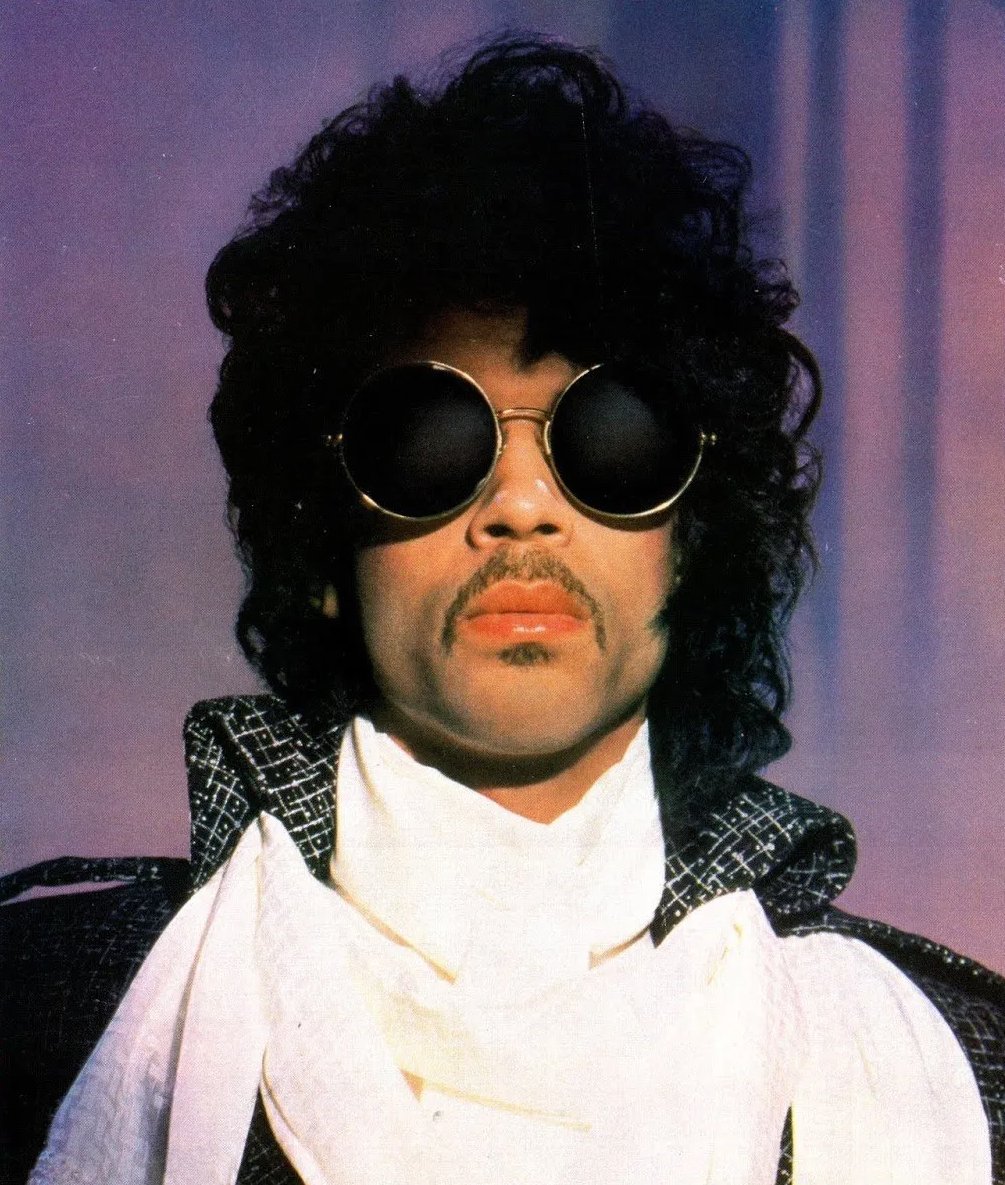

(Featured Image: Prince gazes into the future on the sleeve of the “When Doves Cry”/“17 Days” single; photo by Larry Williams, © Warner Bros.)

Footnotes

- Dave Simpson, “‘He sang the part of a lonely person’: the story of 17 Days, a lost Prince masterpiece,” The Guardian, September 6, 2018. ↩︎

- Duane Tudahl, Prince and the Purple Rain Era Studio Sessions: 1983 and 1984 – Expanded Edition (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), p. 133. ↩︎

- Simpson. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Michael Galluci, “Prince Exiles One of His Best Songs, ’17 Days,’ to a B-Side: 365 Prince Songs in a Year,” Diffuser, April 27, 2017. ↩︎

- Tudahl, p. 134. ↩︎

- K Nicola Dyes, “The Voice: Brenda Bennett Talks 2 Beautiful Nights,” Dyes Got the Answers 2 Ur ?s, April 4, 2014. ↩︎

- Tudahl, p. 172. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 173. ↩︎

- Lisa Coleman, “Notes on a Cassette Tape,” liner notes, Piano & A Microphone 1983 Deluxe Edition, music by Prince, Warner Bros./NPG Records, 2018, p. 3. ↩︎

- Jill Jones, “Memories & Musings…”, Ibid., p. 7. ↩︎

- Tudahl, p. 221. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Hanif Abdurraqib, “The Delicious Misery of the ‘Sad Banger,’” The New York Times Magazine, March 11, 2022. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 296. ↩︎

Leave a Reply