Note: I was just over 1,800 words into the post you’re about to read when I finally admitted defeat; there is, quite simply, no way that I can fit everything I have to say about “Purple Rain” into a single, digestible piece of writing. So, in the grand tradition of my “Controversy” three-parter from 2018, I’m splitting it into chapters. The first, and likely longest, will talk about the song’s composition; the second will go into detail about its debut performance at First Avenue on August 3, 1983; and the third will delve into the final recording that appears on the Purple Rain album and film. There will probably also be a coda of some kind discussing the song’s impressive (and ongoing) afterlife. Basically, just think of July 2021 as my unofficial “Purple Rain” month–and, for the next several weeks, sit back and let me guide u through the purple rain.

It’s a sweltering August night at First Avenue in downtown Minneapolis. Prince and his band have just returned to the stage for the first encore of their benefit show for the Minnesota Dance Theatre: the local dance company and school, located just up the street at 6th and Hennepin, where the musicians have been taking dance and movement classes to prepare for their imminent feature film debut. Moments earlier, MDT founder and artistic director Loyce Houlton thanked Prince with a hug, declaring, “We don’t have a ‘Prince’ in Minnesota, we have a king.” Before that, Prince had run the group through a fierce 10-song set: sprinkling a handful of crowd-pleasers amongst the largely new material, and ending with the biggest crowd-pleaser of all, his Number 6 pop hit “Little Red Corvette.”

No one in the sold-out crowd of around 1,500 recognizes the chords that now ring out from the darkened stage. Even the film’s director, Albert Magnoli, hasn’t heard the song before; it wasn’t among the tapes he’d reviewed to prepare for his draft of the screenplay. But the chords–played by 19-year-old guitarist Wendy Melvoin, in her first public performance with Prince–are immediately attention-grabbing: rich and colorful and uniquely voiced, somewhere between Jimi Hendrix and Joni Mitchell.

A spotlight shines on Wendy as she continues to play, her purple Rickenbacker 330 echoed by her partner Lisa Coleman playing the same progression on electric piano. Prince begins to solo around the edges of the progression; he paces the stage, walking out to the edge of the crowd as he plays, then slings his “Madcat” Telecaster around his back and makes his way to the microphone at center stage. He holds the mic for an instant and backs away, as if suddenly overwhelmed. Then, he steps back to the mic and begins to sing: “I never meant 2 cause u any sorrow…”

Verse 1

The origins of “Purple Rain” are murkier than the rest of the album that shares its title: No one seems to recall from where, precisely, the song emerged–even as everyone seems to have played a role in its conception.

According to the musicians who shared the stage with Prince that fateful night in August 1983, the story begins with a humble acoustic demo. Prince “thought it was just a country song,” keyboardist Lisa Coleman told BBC Music (Savage 2018). In this telling (a little conveniently), “Purple Rain” didn’t become “Purple Rain” until the Band Later Known as the Revolution got their hands on it: As drummer Bobby Z claims in the liner notes for the album’s 2017 expanded edition, each member “added just enough of themselves to make it whole” (Revolution 24).

But there are other versions of the story, as well. In her own liner notes for 2018’s Piano & A Microphone 1983, associated artist Jill Jones intimates that “Purple Rain” was a “collaboration” between Prince and his father, John L. Nelson, which the former “refin[ed]… and expand[ed]” (Jones 2018 8). The weirdest account, meanwhile, comes from Fleetwood Mac singer Stevie Nicks. Prince and Nicks had previously collaborated on her “Little Red Corvette”-indebted hit “Stand Back,” as well as another song, tentatively titled “I Know What to Say to You,” that remains unreleased. At some point, he sent her a demo tape of a long, mostly instrumental tune, and invited her to write lyrics. “It was so overwhelming, that 10-minute track, that I listened to it and I just got scared,” she later recalled to Jon Bream of the Minneapolis Star Tribune. “I called him back and said, ‘I can’t do it. I wish I could. It’s too much for me.’ I’m so glad that I didn’t, because he wrote it, and it became ‘Purple Rain’” (Bream 2011 “Stevie”).

It was so overwhelming, that 10-minute track… I just got scared.

Stevie Nicks

There are, at least, a few things we know for sure about the evolution of “Purple Rain,” thanks to recordings that have leaked into the bootleg market. We know, for example, that Prince was playing around with the song’s chord progression as early as the previous year: A solo work tape, dated (perhaps erroneously) “early 1982,” is now circulating which features a lengthy riff on what would become “Purple Rain,” alongside sketches of “Something in the Water (Does Not Compute),” “Katrina’s Paper Dolls,” and “Lisa.” Unaccompanied save for the pulse of his Linn LM-1, Prince plays the familiar, ethereal chords over a lively synth-bassline; his voice is too drenched in reverb to make out many words beyond the refrain, “All the kids are talkin’ ’bout it’s all about the get down.” Eventually, the bassline drops out and he continues playing the main progression, shifting to a more plaintive refrain around the words, “I’ve gotta shake this feeling.” It’s possible, in fact, that this tape is the very one that would later “scare” Stevie Nicks; in a 2013 interview with U.K. music magazine Mojo, Nicks recalled a “whole instrumental track and a little bit of Prince singing, ‘Can’t get over that feeling’, or something” (Jones 2013).

Another glimpse into the prehistory of “Purple Rain” comes from Prince’s posthumous memoir, which includes among its various ephemera a previously-unseen early draft of the lyrics. The draft–written, one presumes, in the spring or early summer of 1983–starts out similar to the version performed at First Avenue, with only a few minor differences in word choice: “I never meant to fill your life with sorrow,” it begins, “I never meant to cause u any pain / I only wanted to one time see u laughing / I only wanted to see u bathing in the Purple Rain.” The second verse, meanwhile, is more or less exactly as recorded–its sole divergence, “I only wanted to be your purple friend,” ultimately crossed out and replaced with the familiar, “some kind of friend” (Prince 2019 228).

On the draft’s second page–which the memoir, oddly, prints first–a few other interesting changes come into view. The third verse approximates the finished song’s lyrics about needing a “leader”; but the specificity of the line, “let your darling Prince guide u,” makes it clear that at least at this early stage, the suggestion was coming from Prince himself, rather than his movie character or Jesus Christ. Some deleted lines from the fourth verse (moved up to third for the First Avenue performance, and ultimately deleted from the album cut) also read as editorializing from the notoriously control-hungry artist: “I want control. I’ve got the keys[,] now gimme the driver’s seat. Try it” (Prince 2019 227).

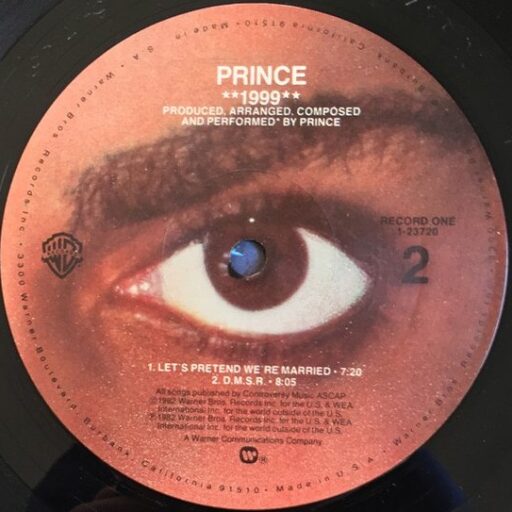

It’s on the third and final page, though, that the real departures become evident. Breaking from the established meter of the earlier verses, the lyrics read, “I promise I won’t hurt u / Trust me / Trust me / I’m not a politician, I’m a purple musician / and I only want to set u free” (Prince 2019 229). The repeated references to Prince and his music make this early draft of “Purple Rain” feel more like an artistic statement of intent, in the tradition of 1999-era tracks like “D.M.S.R.” or “Purple Music,” than the more universal anthem it would eventually become; they also contradict Coleman’s inference that Prince thought of the song as “for Willie Nelson or Dolly Parton,” rather than something to record himself (Savage 2018).

But it’s here that the primary sources leave off, so we must rely on Coleman and her bandmates to fill in the blanks. Wendy Melvoin recalled hearing the song for the first time on December 12, 1982, during a soundcheck at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Coliseum. “I remember him coming in, and he had this idea,” she told journalist Alan Light. “He made it clear: ‘I need to find this thing; it needs to be this and it has to be this tempo,’ and then he picked a key and we started jamming and came up with that opening chord sequence, and it just started to happen” (Light 79). The chords, again, are key: “When Wendy… played those chords on guitar,” Coleman recalled, “it changed [Prince’s] mind about what the song could be. I remember his face: ‘How do you do that?’ It ignited him and the rest of us” (Bream 2017 “Revolution”).

While some aspects of the Revolution’s version of events leave me feeling skeptical, credit where it’s due: Wendy’s chords really are magnificent. In the liner notes to the Purple Rain deluxe edition, she recounts with well-earned pride the time Joni Mitchell (no stranger, herself, to a beautifully-voiced guitar chord) asked if she’d used open tuning to achieve the sound. “As someone whose measure of personal best was based on the greatness of Prince and Joni,” Melvoin writes, “I was happy to say, ‘Nope, my thumb is my weapon’” (Revolution 24). Melvoin took Prince’s original chords and inverted them, adding complexity and interest: as she explained in 2004, “We kept all those suspended chords… then I put the [ninth] in there” (Tudahl 2018 106).

From this foundation, Prince and the band hammered out the arrangement over a marathon series of rehearsals in summer 1983. At one point, keyboardist Dr. Fink improvised a high-register piano line, which would later transform into the keening melody that launched a thousand audience singalongs: it “came from me, just by sheer accident,” he recalled, and Prince “latched onto it and sang it” (Light 80). Rehearsing the song, Coleman writes in the liner notes, “was like dancing together. We listened to each other with such intensity that I felt we all were hitting the crash cymbal when Bobby hit it… Wendy’s beautiful guitar voicing informed Prince’s melody, and [bassist] Brownmark’s sensitivity to supporting a verse, and then doubling up on the outro with the descending line, all came organically that day” (Revolution 23).

However one might feel about the Revolution’s claim to joint authorship, it is precisely this “organic” accumulation of influences that gives “Purple Rain” its lasting power. The country feel Coleman noted in Prince’s demo is still very much evident in the final song–so much so that, when bodyguard and avid country fan “Big Chick” Huntsberry heard it at rehearsal, his reaction was reportedly to exclaim that “Willie Nelson’s gonna cover it” (Light 81). But the song isn’t, as Fink later argued, strictly “mainstream, midwestern United States rock and roll” (Tudahl 2018 106). Instead, it’s as sterling an example as I can name of what country-rock forefather Gram Parsons dubbed “Cosmic American Music”: a freewheeling amalgamation of blues, country, gospel, soul, and rock and roll that dissolves the boundaries between Black and White, counterculture and “straight.” As Coleman put it, “We had struggled for a couple of years, trying to write one song for a black music station, and one for a rock station. But [‘Purple Rain’] was played on every kind of radio station” (Hasted 2019).

We had struggled for a couple of years, trying to write one song for a black music station, and one for a rock station. But [‘Purple Rain’] was played on every kind of radio station.

Lisa Coleman

Still, Fink’s “midwestern rock and roll” comment wasn’t entirely off the mark–at least, if two particular stories are to be believed. The first comes from Dr. Fink himself: “When we were out on the 1999 tour,” he recalled, “Bob Seger was shadowing us, playing everywhere we went. Prince said, ‘I don’t understand the appeal of that stuff.’ I go, ‘It’s like country-rock, it’s white music. You should write a ballad like Bob Seger writes and you’ll cross right over’” (Nilsen 1999 129). In a 2015 interview with writer Miles Marshall Lewis, Prince would balk at the notion of Ur-heartland rocker Seger as an inspiration for his trademark song: “Y’all got to have everything, huh?” he rolled his eyes, alluding to the canonization of White, Baby Boomer-era “classic rock” at the expense of other, Blacker styles (Lewis 2015). And yet, in a classic Prince contradiction, he had in fact shouted out Seger a little over a decade earlier, when both artists were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: writer Rick Coates quotes him as saying that Seger “had a lot of influence on me at the start of my career; he certainly influenced my writing” (Coates 2004).

Even if one can’t accept “Purple Rain” as Prince’s “Turn the Page,” there is solid evidence that he took inspiration from another famed rock ballad: Journey’s “Faithfully,” which as blogger Anil Dash notes was reaching its peak on AOR radio just as Prince and his bandmates were honing “Purple Rain” in rehearsal. The two songs share a number of striking similarities, including a comparable chord progression, a soaring, wordless vocal hook (compare Journey singer Steve Perry’s “Oh, oh, oh, oh” with the “woo-hoo-hoo-hoo” Prince adapted from Fink’s piano line), and a climactic guitar solo. So striking were the similarities, in fact, that Prince seems to have worried they were legally actionable; in early 1984, according to Journey’s keyboard player and “Faithfully” songwriter Jonathan Cain, Prince called to play him the chord changes from “Purple Rain” and, in his words, ask him not to sue. Instead, Cain recalled to Billboard, “I told him, ‘Man, I’m just super-flattered that you even called. It shows you’re that classy of a guy. Good luck with the song. I know it’s gonna be a hit’” (Graff 2016).

Cain’s instincts–and Fink’s, for that matter–were right. “Purple Rain” was, in Wendy Melvoin’s words, “one of those undeniable BIC lighter songs”: the first real one in Prince’s catalogue, an anthem to a degree that previous attempts like “Free” and “Moonbeam Levels” had only hinted at (Tudahl 2018 107). But it’s also more than than that. Where a similar song like “Faithfully” remains encased in the amber of early-’80s AOR, “Purple Rain” feels timeless, even genreless: the kind of perfect confluence of composition, performance, and historical moment that only a handful of artists ever live to achieve. It’s lightning in a bottle. And on August 3, 1983, Prince and the Revolution captured it.

That’s all for now! I’ll be back soon with Part 2.

“Purple Rain”

Electric Fetus / Spotify / TIDAL

Leave a Reply