The popular narrative holds that Prince didn’t start working in earnest on Sheila E.’s album until after they’d recorded “Erotic City” together; pay attention to his early 1984 session history, however, and it becomes clear that he’d been toying with the project for some time. For a case in point, one need look no further than the week of February 6. On Monday, Prince assembled the first compilation for the Apollonia 6 album. By Tuesday, he had returned to his own music, making heavy use of Sheila’s talents in the studio; this was the date when their chemistry while recording “God (Love Theme from Purple Rain)” spurred Peggy Mac to suggest they get a room. Wednesday was the session when Sheila added her drums to “The Glamorous Life”–and immediately commandeered the song from Apollonia 6. It thus seems no coincidence that on Friday, Prince cut “The Belle of St. Mark”: a song for a female artist that was pointedly not intended for the beleaguered girl group.

Like “The Bird,” “Jungle Love,” and “Bite the Beat,” “Belle” was based on an instrumental demo by the Time’s Jesse Johnson; to his lieutenant’s frolicsome rhythm track and synth hook, Prince joined a fanciful narrative about a girl who’s fallen head over heels for the eponymous “frail but passionate creature.” This “Belle” (not, intriguingly, “Beau”) is an exemplar of what Prince biographer Dave Hill identifies as the key male “type” on The Glamorous Life: “beautiful men-children who sin with the chaste eyes of cherubs.”1 He is clearly European–French, to be precise, if one goes by his moniker and the verse about his “Paris hair… blow[ing] in the warm Parisian air.” But the reference to “St. Mark” and punning play on the English word “bell” also link him to another place on Prince’s circa-1984 mood board: Venice, Italy, where at the turn of the 16th century an elaborate clock tower was erected to mark the gateway between the city’s religious and political center, the Piazza San Marco (or St. Mark’s Square), and its main commercial artery, the Rialto. Among the tower’s features–along with a huge astronomical clock tracking not only the time of day, but also the phases of the moon and the position of the Sun amidst the zodiacal constellations–was a terrace with two massive bronze mechanical figures that would strike the hour on a literal “bell of St. Mark.”

St. Mark’s Square also was–and, in its contemporary revival, still is–the main site for the Carnevale di Venezia, a local variation on the pre-Lenten festivities observed throughout the Catholic world since the Middle Ages. In Venice as elsewhere, Carnival offered a temporary relief from the day-to-day strictures of the Church: the freedom, in the words of historian Peter Burke, “to eat and drink gargantuan amounts, to wear a mask, to insult your neighbors, to pelt them with eggs, lemons, oranges, etc., and to sing songs full of political or sexual innuendos” (you’re probably beginning to see the appeal for Prince).2 By its 18th-century zenith, Venice Carnival had evolved into a playground for the European aristocracy, with travelers from across the continent drawn to the city for its sanctioned hedonism, fueled by a thriving local industry in papier-mâché masks. “To them, the carnival of Venice meant a holiday from morality, where disguise made all things possible,” writes historian James H. Johnson. “Cover the face, alter the voice, and anything could happen. Naturally the most thrilling possibilities were sexual.”3 This erotic dimension of Carnival, immortalized in the memoirs of Giacomo Casanova, is likely what inspired the masquerade iconography that crops up throughout the Purple Rain era: in Mary Lambert’s music video for “The Glamorous Life,” in the stage design for the tour, and even in the Kid’s bedroom decor in the film.

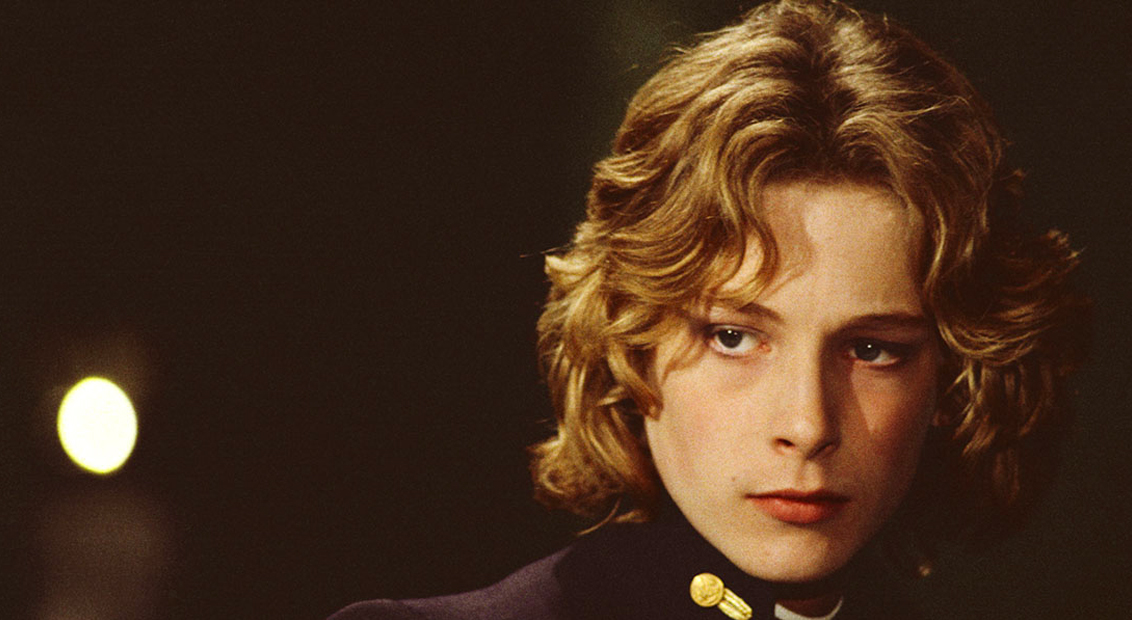

Another Venetian connection can be found in the line about the “Belle” being “only a mere seventeen.” The concept of a feminine-coded, beautiful boy evokes Death in Venice: Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella, adapted for the screen by Luchino Visconti in 1971, which tells the story of an aging artist (a writer in the book, a composer in the film) who becomes transfixed by a seraphic adolescent boy while a cholera epidemic tears through the titular city. In Visconti’s film, the breakout role of 14-year-old Tadzio was played by 15-year-old Björn Andrésen, who was quickly christened “the most beautiful boy in the world” by the international press (not to mention sexually harassed by the staff of a local gay bar after the movie’s Cannes premiere). Known cinephile that he was, Prince may have had Andrésen in mind when he conceived the character of the “Belle.” Certainly, St. Mark’s itself is a consistent presence in the film: from the opening sequence, when the boat carrying Dirk Bogarde’s Gustav von Aschenbach pulls into the San Marco basin; to the sequence when Ashenbach follows Tadzio and his family out of St. Mark’s Basilica over the pealing of the clock tower bell; to, finally, the scene when a Banca Commerciale Italiana clerk on the Square warns him of the plague that will ultimately claim his life.

Of course, the “Belle” had another inspiration from significantly closer to home. With his “ebony hair,” propensity for wearing “clothes that belonged to his father,” and dislike of “talk[ing] to strangers,” he joins the title character of “Oliver’s House” and the lingerie department gigolo from “The Glamorous Life” as a thinly-veiled stand-in for his creator. That, at least, was Sheila’s interpretation: In her 2014 memoir The Beat of My Own Drum, she asserts that she wrote the song’s lyrics “about Prince.”4 Like many of her claims of authorship for her debut album, this appears to be an exaggeration with a kernel of emotional truth. Prince was, by most accounts, the song’s sole writer (with the obvious exception of the elements he pilfered from Jesse); yet it’s hardly a stretch to imagine him drawing on his protégée’s burgeoning feelings for a touch of verisimilitude. There’s even the possibility that the song doesn’t allude to the Piazza San Marco at all, but rather to St. Mark’s Episcopal Cathedral in North Minneapolis–home to a bell tower that Prince would have heard often in his youth. If nothing else, he seemed to embrace the title as yet another of his alter egos: His own name appears nowhere in the album credits, but there’s a “special thanks” to “The Belle Of St. Mark.”

I really thought and believed that ‘Glamorous Life’ should be the first single… I was able to play a solo and I just thought that it was important to showcase me as an artist.

Sheila E.

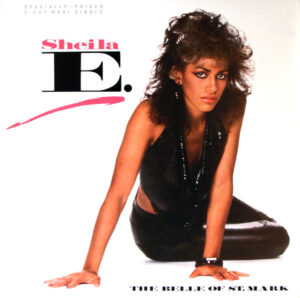

Whoever may have inspired it, Sheila’s performance as a lovesick ingénue–recorded, like the rest of her vocal tracks, over less than a week in late March and early April–is among the album’s most convincing, lending just the right balance of melodrama and guilelessness to the teenage diary entry of a chorus: “I’m in love, I’m in love, I’m in love with the Belle of St. Mark / And if he doesn’t love me, I think I’ll probably die.” This potent combination of impassioned delivery and emotional clarity goes some way toward explaining why Warner Bros. initially earmarked “Belle” for The Glamorous Life’s lead single, rather than the retrospectively obvious choice of the title track. To the jaundiced ears of a record executive, “Belle” simply sounded like the bigger hit: no jazzy saxophone breaks or ambiguous sexual encounters, just good, clean teenage lust and an unrelentingly chipper synth line. In the end, though, Sheila and Prince “fought hard” for their choice, and won.5 “I really thought and believed that ‘Glamorous Life’ should be the first single,” Sheila told Billboard in 2019. “We didn’t know very many women, if at all, during that time in 1984 that… would be playing timbale… I featured a lot of percussion on [‘Glamorous Life’]. It was a dance track. I was able to play a solo and I just thought that it was important to showcase me as an artist.”6

As if to prove her point, when “Belle” was released in October as the album’s second single, it underperformed compared to its predecessor, peaking at Number 34 on the Billboard Hot 100 and only Number 68 on the Hot Black Singles chart. This should come as no surprise: While “Glamorous” sounded tailor-made for Sheila’s particular talents (even if it wasn’t), “Belle” was well-crafted but faceless, embodying the essentialist cynicism of the publishing imprint Prince used for his female side projects: “Girlsongs.” Sheila may acquit herself just fine as a singer, but there’s nothing here that Vanity, Apollonia, or Jill Jones (whose backing vocals are clearly audible on the final track) couldn’t do as well. Most notably, “Belle” is one of only a handful of songs on the album that fails to showcase her chops as a musician, confining her instead to purely auxiliary bongos and sleigh bells. The 12″ “Dance Remix,” created by engineers David Leonard and Coke Johnson in early August, attempts to correct this oversight by making extensive use of the bongo part; but its interminable looping only underscores the thinness of the source material. A much livelier listen is B-side “Too Sexy”: a bona fide original composition by Sheila and her band–albeit one with an unmistakable debt to “All the Critics Love U in New York”–climaxing with her going hog wild on the timbales.

Meanwhile, Prince would make amends for “borrowing” Jesse Johnson’s original demo–albeit in a way that only furthered the growing rift between them. According to engineer Susan Rogers, Prince called from L.A. while Johnson was using his home studio to record some of his own material: “Prince asked Jesse if it was okay that he gave Jesse writing credit on one of Sheila’s songs,” she recalled. “Jesse said, ‘Okay, I guess so. What’s the name of the song?’ Prince said, ‘Shortberry Strawcake, bye-bye.’” It wasn’t until the album came out in June that he realized the credit was to make up for his unacknowledged contributions to “Belle”: “So Jesse gets credit for songwriting, but it is not for the song he wrote. Very weird, and Jesse was very offended.”7 It was another bizarre episode in a relationship that was rapidly approaching its inglorious conclusion: By the end of the month, Johnson and the rest of the Time had officially split, leaving Prince without an opening act for the upcoming tour. Luckily, he wouldn’t have to go far to find a replacement.

(Featured Image: The original “Belle of St. Mark,” Björn Andrésen, in Death in Venice, Luchino Visconti, 1971.)

Footnotes

- Dave Hill, Prince: A Pop Life (Faber, 1989), p. 139. ↩︎

- Peter Burke, “Le carnaval de Venise: Esquisse pour une histoire de longue durée,” Les jeux à la Renaissance, ed. Philippe Ariès and Jean-Claude Margolin (J. Vrin, 1982); quoted in Gilles Bertrand, “Venice Carnival from the Middle Ages to the Twenty-First Century,” Journal of Festive Studies Volume 2 Number 1 (Fall 2020), p. 81. ↩︎

- James H. Johnson, Venice Incognito: Masks in the Serene Republic (University of California Press, 2017), p. 22. ↩︎

- Sheila E. with Wendy Holden, The Beat of My Own Drum: A Memoir (Atria Books, 2015), p. 191. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Rebecca Schiller, “Sheila E. Recalls Hearing Her Song on the Radio the First Time–Just as She Was Getting in a Car Crash,” Billboard, December 13, 2019. ↩︎

- Duane Tudahl, Prince and the Purple Rain Era Studio Sessions: 1983 and 1984 – Expanded Edition (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), p. 266. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to C Liegh McInnisCancel reply