Of the six new, original songs Prince debuted at First Avenue on August 3, 1983, three–“I Would Die 4 U,” “Baby I’m a Star,” and “Purple Rain”–were sourced directly from the concert recording for his upcoming album and film. A fourth, “Let’s Go Crazy,” was re-recorded in short order at the Warehouse rehearsal space; while a fifth, “Electric Intercourse,” never saw official release in Prince’s lifetime. But it was the sixth–a cerebral punk-funk workout called “Computer Blue”–that would occupy Prince for the rest of the month, with weeks of overdubs spanning both Minnesota and L.A.

“The genesis of “Computer Blue” was in the intensive summer 1983 rehearsals at the Warehouse in St. Louis Park. As keyboardist Dr. Fink recalls in the liner notes for the 2017 expanded edition of Purple Rain, “We were jamming at rehearsal one day and I started to play a synthesizer bass part along with the groove. It happened to catch Prince’s ear, so he had our sound man record the jam.” The band continued to work on the song and, according to drummer Bobby Z, had it “just about fully rehearsed” when Prince threw another element into the works: a lyrical guitar solo based on a melody by his father, John L. Nelson, later dubbed “Father’s Song.”1 Along with these borrowed ingredients, Prince also returned to the well of two of his own songs, “Automatic” and “Something in the Water (Does Not Compute)”: neighboring tracks from Side 3 of 1999 that shared a nervy New Wave sensibility and lyrics that literalized the mechanics of love and lust. Even Fink’s aforementioned synth-bass squiggle sounds like a funkier revision of the malfunctioning-robot lead line in “Something in the Water.”

I started to play a synthesizer bass part along with the groove. It happened to catch Prince’s ear, so he had our sound man record the jam.

Dr. Fink

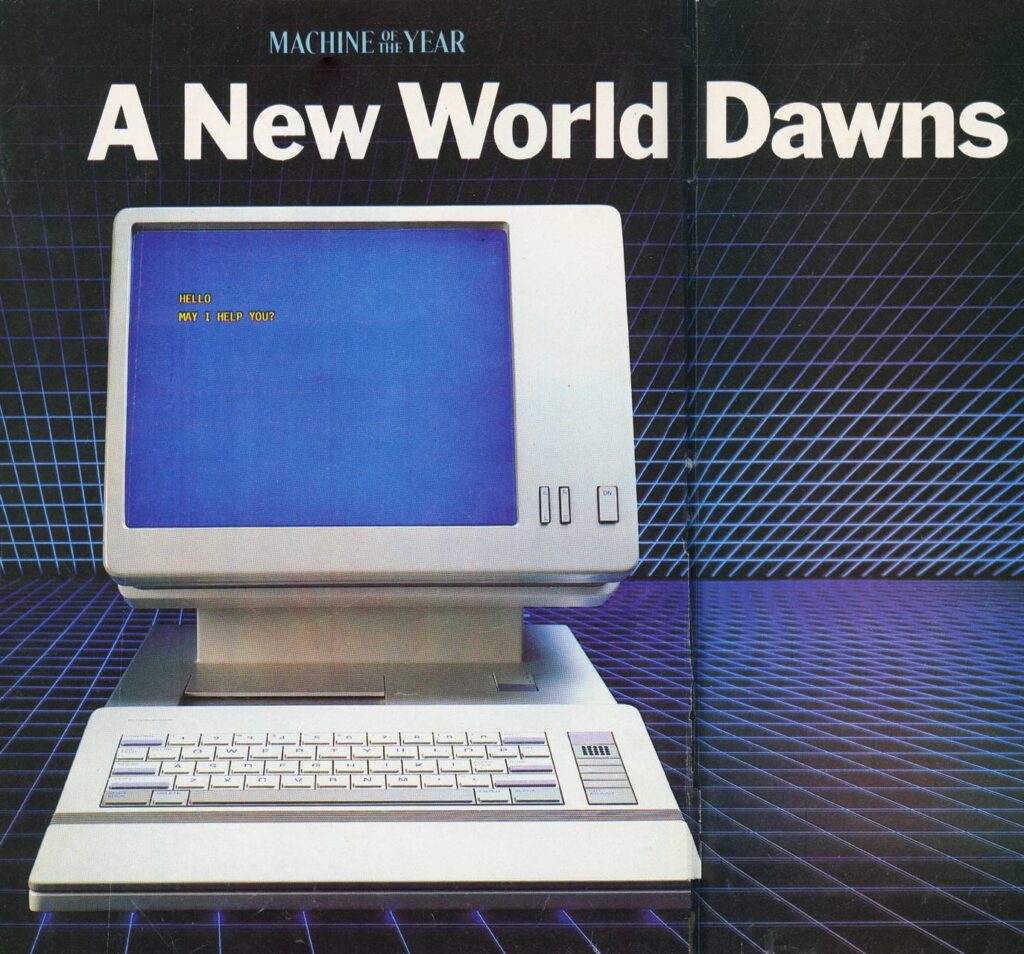

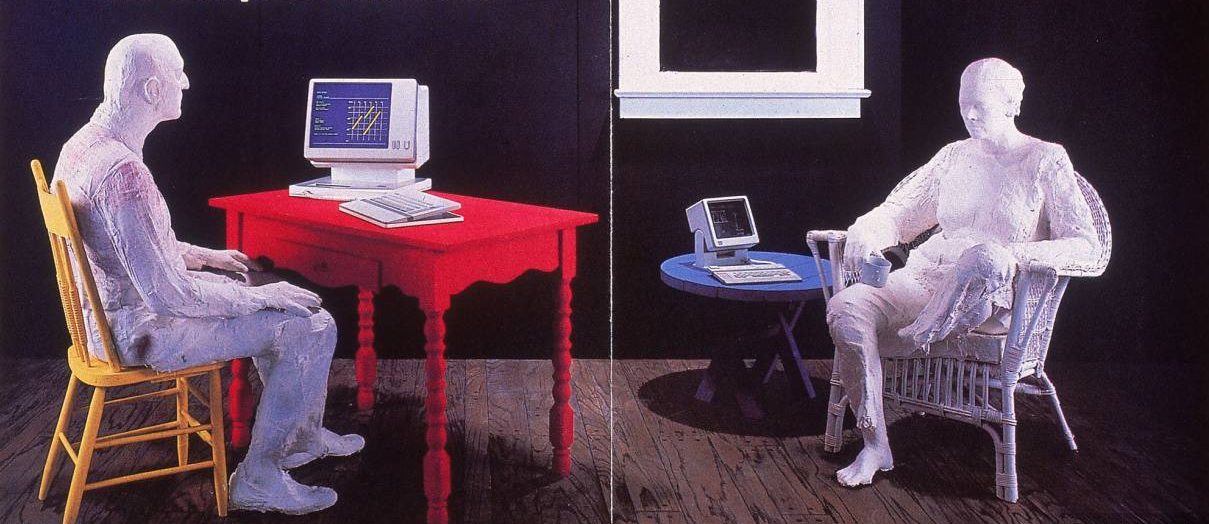

What made this latest iteration distinct was, in part, its timeliness. The previous year had been a watershed for the device known as the personal computer, with TIME magazine reporting industry-wide sales of 2.8 million units in 1982: double the 1.4 million units reported in 1981, and double again the 724,000 units reported in 1980.2 That December, TIME awarded its annual “Man of the Year” title (or, in this case, “Machine of the Year”) to the PC: the first and, to date, only instance of this honor being bestowed upon an inanimate object. In the accompanying 21-page spread, journalist Otto Friedrich laid out the myriad changes widespread PC adoption promised to make “in the way people live and work, perhaps even in the way they think.”3

Notably absent from Friedrich’s article was any discussion of the PC’s potential impact on matters of the heart–or, as the case may be, the loins. To fill this gap in the literature would require the input of a specialist. “Computer Blue” thus finds Prince in the role of a rogue artificial intelligence: querying his internal database for a “love life,” finding it lacking, and dispassionately observing that “there must be something wrong with the machinery.” The chorus is an error message set to music: “until I find that righteous 1 / computer blue.” It’s also a double meaning, the word “blue” referring both figuratively to a melancholy mood, and literally to the bluish-tinged light of a color CRT monitor. Intentionally or not, Prince’s portrayal of a sentient, lovelorn CPU tapped into contemporary anxieties around the emergent technology: namely, that society’s increasing dependence on computers would have a dehumanizing effect, with cold logic taking the place of feelings and empathy. “Computer Blue” plays up this tension in the contrast between the robotic lyrics and the decidedly human expressiveness of Prince’s vocals, which run the course from a plaintive whimper to an impassioned scream–not to mention his guitar solos, which have a nuance and sensitivity that no computer, then or now, could hope to match.

Those guitar solos would take center stage in the song’s debut at First Avenue–and, for that matter, every performance thereafter. For the first solo, Prince shreds on what noted guitar virtuoso Cory Wong describes as a “16th note chromatic motif that is dissonant but still feels like a hook,” while second guitarist Wendy Melvoin genuflects before him. This feat of dexterity is followed by a synth-led breakdown, against which he plays a second solo interpolating “Father’s Song”: “a written out hook,” explains Wong, “that gets doubled with the piano but slips in and out of some improvised lines.”4 Next, with a shout of, “The computer’s on the verge of a breakdown!”, Prince fires off a third solo, splitting the difference between the frenetic first and the more controlled, melodic second. At last, leading the band in a final repetition of the hook, he spins, drops to his knees, and ends the song with a flourish before sauntering back to the front of the stage and tossing his pick into the crowd.

“Computer Blue” was an obvious highlight of the First Avenue show; but, just as he had with “Let’s Go Crazy,” Prince decided that he could do better. On August 8, the day after tracking the album version of “Let’s Go Crazy,” the band reconvened at the Warehouse to record a new basic track from scratch. The result, according to sessionographer Duane Tudahl, was a massively expanded jam, over twice the length of the take recorded live the previous week. It was this, 14-minute version of “Computer Blue” that Prince took with him to Sunset Sound a week later, with the intention of fleshing it out into his latest–and most ambitious–epic. Such were his ambitions, in fact, that for the first time since he began recording at Sunset Sound, Prince found himself chafing against the studio’s 24-track recording capabilities. Engineer Peggy McCreary recalled, “All of a sudden he wanted to add things like strings and I said, ‘Excuse me. We only have twenty-four tracks. We don’t have enough room.’ And he just said, ‘Make some more.’”5 Her solution was to hook up a second 24-track console, effectively doubling the number of tracks available to Prince–not to mention the amount of work for his engineers. To help keep up with the session’s demands, McCreary brought in her fellow engineer (and fiancé), David Leonard, who orchestrated some of the more technical tasks: “I triggered [s]ynths off of hi-hats and stuff like that,” he remembered.6

All of a sudden [Prince] wanted to add things like strings and I said, ‘Excuse me. We only have twenty-four tracks. We don’t have enough room.’ And he just said, ‘Make some more.’

Peggy McCreary

From August 15-21–and then again from August 29-31–Prince, McCreary, and Leonard proceeded to fill up all 48 of the available tracks. Among the additions was a percussive synth line borrowed from the live arrangement of “Automatic” (compare the passage at 4:12 of the song’s November 30, 1982 performance at Detroit’s Masonic Hall, released on the 1999 Super Deluxe Edition, to the one at 6:32 of the extended “Computer Blue” from the expanded edition of Purple Rain). But this wasn’t the only callback. Also returning from “Automatic” was its Greek chorus of fembot tormentors, played here by Wendy Melvoin and her keyboardist bandmate/girlfriend, Lisa Coleman.

It’s these spoken-word elements that would turn “Computer Blue” into more than just a series of (admittedly face-melting) guitar solos. The most beloved–if only because it’s the one most listeners have heard–is the exchange that opens the song, in which Robo-Lisa asks Wendy-tron if the “water [is] warm enough” for a mysterious and no-doubt kinky ritual. According to Coleman, the dialogue’s inciting incident was remarkably straightforward: Prince “literally handed me a piece of paper in the studio and said[,] [‘]Would you say this?[’]” she told Jon Bream of the Minneapolis Star Tribune. “The words had no meaning in my mind.”7 Melvoin concurred: “We didn’t even think it was this weird psychosexual lesbian thing,” she recalled to biographer Matt Thorne.8

We didn’t even think it was this weird psychosexual lesbian thing.

Wendy Melvoin

More interesting, at least in my book, are the exchanges that didn’t make it onto the final album. Just after Prince wraps up his third guitar solo on the extended studio recording, Wendy and Lisa return to taunt him: “poor lonely computer / it’s time someone programmed u / it’s time u learned love and lust / they both have 4 letters / but they’re entirely different words.” Later, their chiding takes on a more pointedly feminist dimension, as they warn the “chauvinistic computer” that “women are not butterflies,” but “computers too / just like you.” Nor are these the only voices echoing through the computer’s internal memory. In the wake of yet another guitar solo, a double-tracked Prince sings, “We’re on the verge of a breakdown / What is life without love?” His question is answered by an uncredited Bobby Z, screaming, “It’s hell! Computer blue!” In the next verse, Prince calls for his “Father,” exclaiming that “the sun is gone” and imploring, “where is the Dawn?”: a question that could be variously addressed to his earthly father, the father character in his nascent film, or God the Father Himself. The lines that follow suggest a combination of all three, neatly nailing the crux of his interpersonal struggles with a soupçon of Christian guilt: “Should I go to church on Sundays? / Should I stay home and pray? / Should I try to make her happy? / Should I try to make her stay?”

Headiest of all is the section that would give the extended “Computer Blue” its informal subtitle (and, with its official release in 2017, its formal one as well): the “Hallway Speech.” His voice buried in a tumult of synthesizers, programmed drums, and his own croons and screams, Prince narrates the procession of two characters–a man and a woman–through a series of hallways named after emotions, each “vastly different from the next”: “Lust,” “Fear,” “Insecurity,” and “Hate.” In the end, the woman disappears, and the man proceeds alone through the hallway named “Pain.”

Like many of his more eccentric flourishes, the “Hallway Speech” seems to have begun life as Prince’s take on an existing template. Tudahl observes similarities between the segment and the neurotic hipster-rap of “AEIOU Sometimes Y” by New York synthpop duo Ēbn-Ōzn: a contemporary club and MTV hit that made headlines as the first U.S. single to be recorded entirely on a computer (the Fairlight CMI, to be precise). Music journalist Alan Light, meanwhile, finds the speech “[v]aguely reminiscent of Jim Morrison’s recited section in the Doors’ epic ‘The End,’” in which an unnamed “killer” stalks the halls of his family home, ending in an Oedipal confrontation with his parents.9

Where Prince makes the “Hallway Speech” his own is in its exploration of one of his pet themes: a yearning for connection, thwarted by a deep-seated fear of abandonment. As they make the “long walk to his bedroom,” the male and female protagonists must first run the hallways’ gauntlet of emotions; but with every passing corridor, she pulls further away, until at last he’s left to face the empty house alone. Combined with the recurring scoldings from Wendy and Lisa, the scenario was Prince’s frankest acknowledgment to date of his struggles with intimacy: the same perpetual conflict that inspired the plot of Purple Rain, not to mention the real-life drama behind the scenes of the 1999 tour.

With its epic length, dense arrangement, and probing psychological insight, “Computer Blue” looked poised to become the musical centerpiece of Purple Rain upon its completion at the end of August. And, at least for a while, it was: The album’s first configuration on November 7 included a 12-and-a-half-minute version of the song, removing only some feedback from the beginning and end of the track. But Prince and his management were determined not to follow 1999 with another double album, and space was soon at a premium. By the second configuration on March 23, 1984, the track had been given another trim. Finally, on April 14, more severe cuts were made to squeeze in a ninth song, “Take Me with U”: chopping the second verse, third guitar solo, and every spoken-word segment save for Wendy and Lisa’s enigmatic opening exchange. Once the dust had settled, “Computer Blue” came to just under four minutes–less than two-thirds the length of the version debuted at First Avenue.

On record, the final incarnation of “Computer Blue” is slight, but intriguing: a glorified extended intro to “Darling Nikki” that still manages to pack in multiple proggy movements and hairpin tonal shifts. On film, it makes even more of an impression. The scene opens with the Revolution already in full swing: the Kid and bassist Brown Mark shirtless and glistening with sweat; the former wearing a sheer black lace eye mask and single black glove for an S&M-chic effect (see above). As the Kid launches into the first guitar solo, Wendy drops to her knees, an echo of her stage blocking from the First Avenue show. For that performance, her kneeling position was a practical consideration, so she could closely follow along with Prince’s intricate picking: “That guitar part, in the entire Prince repertoire that I played over those years, was the hardest thing for me to master,” she recently told writer Andrea Swensson.10 But when recreated on the big screen, with her back facing the audience and her face brushing against the pickguard of his Madcat Telecaster, the effect is unmistakably more suggestive–and it only gets less mistakable when he reaches out a gloved hand to caress her cheek (see below).

It’s fair to read this moment between the Kid and Wendy as just another example of chauvinism in Purple Rain–a film, lest we forget, that also prominently features a woman being thrown in a dumpster. The staging recalls David Bowie miming fellatio on his early-’70s guitarist Mick Ronson (see above), but shatters remarkably fewer taboos; indeed, it smacks of the kind of simplistically macho, phallocentric posturing that wouldn’t be out of place in a Mötley Crüe show. That the real Wendy Melvoin is gay–something Prince knew well, seeing as she was in a committed relationship with his keyboard player–does not improve the optics.

For what it’s worth, however, the version of the scene in Albert Magnoli’s draft screenplay sheds some light on the director’s intentions. Wendy is described as being “made up fiercely” to resemble Prince; their simulated sex act thus creates an “unnerving effect” of “Prince going down on himself.”11 This deeper subtext doesn’t quite translate onto the screen–mostly because in the film, every member of the Revolution ends up looking like a Kid clone, not just Wendy. But the reaction shots of discomfited audience members Billy Sparks, Kim Upsher, and Jill Jones allow us to get the gist that the performance is meant to represent the Kid’s descent into self-fellating narcissism.

Meanwhile, despite the cuts to “Computer Blue” on the album, the ghost in the machine was never fully exorcised. The lyrics sheet for Purple Rain includes the “poor lonely computer” speech in full–attributed here to “the Righteous 1” theirself. Later, on the Purple Rain tour, Prince had a short clip of the speech play over a lull in the song while he put his acting lessons to work, miming desperate glances around the arena to find the voices’ source (see above). It’s clear that, even though it was no longer officially part of the song, Prince considered the critical voice of “the Righteous 1” to be core to its meaning.

And, hey, maybe the cuts were made for good reason. The extended “Computer Blue” unquestionably belongs to a much weirder, darker album than the tightly-calibrated bid for pop supremacy that was Purple Rain. Music writer Jack Riedy also isn’t wrong when he writes that the “hallway speech” is “just a little too faux-tortured,” even by mid-’80s Prince standards.12 It does feel a bit of a shame that it took more than 30 years for a wider audience to hear some of Prince’s most psychologically trenchant lyrics: what the 500 Prince Songs blog calls “an Aladdin’s cave of Prince tropes and ideas,” and a revealing glimpse into the personal angst that fueled not only Purple Rain, but also a hefty portion of his other major work.13 But then, that’s one of the abiding pleasures of his discography: that lurking beneath the surface of even the deepest cuts are depths still lower, there for us to plumb whenever we’re ready.

(Featured Image: Cover of TIME magazine’s January 3, 1983 “Machine of the Year” issue. Sculpture by George Segal; photo stolen from Cult of Mac. This post was edited in August 2024 to add Wendy’s quote about the First Avenue show–a vital piece of the puzzle when it comes to the controversial movie scene! For more on “that” moment, see my podcast episode with Carmen Hoover, who was there to see it happen the first time around.)

Footnotes

- The Revolution, “Fearlessly Breathe In the Purple Rain… The Revolution Track-by-Track,” liner notes, Purple Rain Deluxe Expanded Edition, music by Prince and the Revolution, Warner Bros./NPG Records, 2017, p. ↩︎

- Otto Friedrich, “The Computer Moves In,” TIME, January 3, 1983, p. 1. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 2. ↩︎

- Cory Wong, “Five reasons Prince was a guitar legend,” The Current, April 20, 2017. ↩︎

- Duane Tudahl, Prince and the Purple Rain Era Studio Sessions: 1983 and 1984 – Expanded Edition (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), p. 136. ↩︎

- Jake Brown, Prince ‘In the Studio’: 1975-1995 (Colossus Books, 2010), eBook edition. ↩︎

- Jon Bream, “Revolution keyboardist shares untold stories from Prince’s soon-to-be reissued Purple Rain,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, June 16, 2017, republished on Lipstick Alley. ↩︎

- Matt Thorne, Prince: The Man and His Music – Updated and Expanded Second Edition (Agate Publishing, 2023), p. 101. ↩︎

- Alan Light, Let’s Go Crazy: Prince and the Making of Purple Rain (Atria Books, 2014), p. 77. ↩︎

- Andrea Swensson, Prince and Purple Rain: 40 Years (Motorbooks International, 2024), p. 70. ↩︎

- Albert Magnoli, draft screenplay of Purple Rain (scanned and edited by lovesexy@umich.edu), IMSDb. ↩︎

- Jack Riedy, Electric Word Life: Writing on Prince 2016-2021 (Self-published, 2021), p. 13. ↩︎

- Tora Borealis, “80: Computer Blue,” 500 Prince Songs, May 8, 2019. ↩︎

Leave a Reply