Of the 11 songs that would eventually make their way onto Prince’s fifth album, “Lady Cab Driver” appears to have had the longest gestation period. The song was completed at Sunset Sound on July 7, 1982, the day after “Moonbeam Levels”; but, as the recent Super Deluxe Edition of 1999 revealed, its seeds had been planted during a break in the Controversy tour over half a year earlier on December 8, 1981, in the form of a different song called “Rearrange.”

According to an interview with sessionographer Duane Tudahl for the Minnesota Public Radio podcast The Story of 1999, “Rearrange” was long known to researchers by its title alone: “it was one of those songs that we’d heard existed, but I didn’t think it was actually a song,” Tudahl told host Andrea Swensson. “I thought it was just some shuffling of his stuff”–a studio note indicating a literal rearrangement of tapes. As it turned out, of course, it was real–though it was also little more than an admittedly funky sketch: a stark, mid-paced groove with a slick rhythm guitar hook similar to the Time track “The Stick.”

Given this similarity–not to mention Prince’s guitar solo, which plays neatly to Jesse Johnson’s combustive style–it seems likely that “Rearrange” was at least provisionally mooted for that group. But this is just speculation; ultimately, says Tudahl, we “don’t know whether it was intended for 1999, whether he was searching for a voice for 1999, or whether he was saying, ‘I gotta record another Time album soon.’ But either way it was something that was not planned. He just thought, ‘I’m in the studio, I gotta record… This is what I’m gonna do’” (Swensson 2019 Episode 2).

[Prince] just thought, ‘I’m in the studio, I gotta record… This is what I’m gonna do.’

Duane Tudahl

As a spur-of-the-moment jam, it makes sense that the lyrics of “Rearrange” would center around a topic close to Prince’s heart: his own, groundbreaking fusion of funk and punk. “Rearrange your mind,” he chants, “Man, you’ve got to be drunk / To think we’d stoop so low and play that old-time funk.” Echoing the individualist messages of earlier songs like “Uptown,” Prince presents his Minneapolis Sound as the clarion call for an emergent counterculture: “Rearrange your brain / Got to free your mind / Your hair, your clothes, your body, your soul / Won’t be far behind.” Though perhaps not as musically groundbreaking as many of the other tracks Prince would record for 1999, “Rearrange” is a fine example of his ability to merge genres on the fly, with the bassline’s steady eighth-note figure adding a (different) kind of New Wave tension to the relaxed rhythm guitar groove.

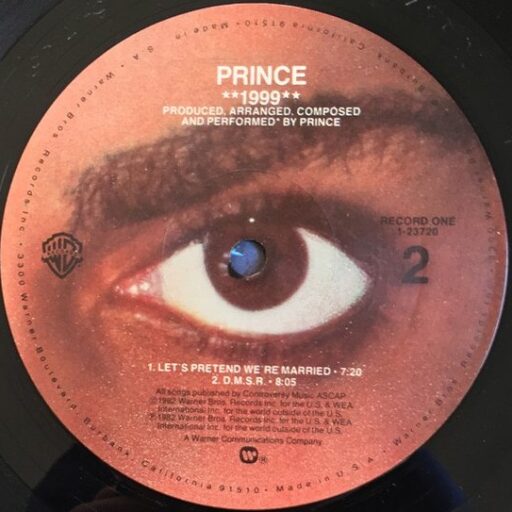

Clearly, Prince was taken enough with “Rearrange” to revisit it seven months later; by that time, though, its premise had been extrapolated and refined through a series of other musical manifestoes–one of which, “D.M.S.R.,” even went so far as to recycle his command to “loosen up your hair.” So, he rearranged: stripping the track to its instrumental backing and repurposing the falsetto chorus for the new song’s verses. In place of the lyrics about rearranging one’s mind is a scenario pulled straight out of a porno, in which Prince (or, at least, a character with whom he shares an uncanny resemblance) is picked up by, and proceeds to rearrange the insides of, the titular female cabbie.

What keeps “Lady Cab Driver” distinct from 1999‘s other transportation-themed erotic fantasies, “Little Red Corvette” and “International Lover,” is its pervasive sense of angst. The song’s use of a taxi cab as a metaphor for social and sexual isolation links it directly with “Annie Christian,” the apocalyptic fever dream at the center of 1981’s Controversy; which, in turn, evokes Paul Schrader’s and Martin Scorsese’s 1976 neo-noir Taxi Driver–not exactly a popular source of titillation, unless you’re John Hinckley, Jr. Perverse as ever, for this vignette Prince takes on a role analogous to Iris, a.k.a. “Easy,” the preteen sex worker played by Jodie Foster in the film: a wide-eyed waif on the run who implores the driver, “Don’t know where I’m goin[’] [‘]cause I don’t know where I’ve been / So just put your foot on the gas–let’s drive.”

Indeed, while “Lady Cab Driver”’s (ahem) climax is as inevitable in its own way as the explosion of violence that concludes Taxi Driver–the moment Prince makes a note of his driver’s gender, it should be obvious where this is going–the song’s first three minutes offer more in the way of ennui than eroticism. Prince certainly does his share of eyelash-fluttering, breathily imploring the driver, “Honey, let’s go everywhere”; but he also asks if she’ll “accept my tears to pay the fare”–an effective flourish of brooding capital-”R” Romance, but not much of a pick-up line. Even the song’s arrangement–arguably the most conventionally funky on the album, with its elastic bassline and live snare layered atop the Linn LM-1’s kick and hi-hat–feels brittle and stark, as cold as the “trouble winds” from which Prince’s character has taken shelter.

Once it hits the three-minute mark, however, “Lady Cab Driver” takes a sharp left into carnality. The action abruptly shifts–either to the backseat of the cab or to the bedroom–and Prince just as abruptly transforms from Easy/Iris into a porn-parody version of Robert De Niro’s Travis Bickle: delivering a righteous monologue while he brings the heretofore silent driver to orgasm, dedicating each thrust to a different social or personal ill. Several of these ills should be familiar from other entries in the early-’80s Prince canon: the line about “politicians who are bored and believe in war” echoes “Partyup”; the repeated references to “the tourists at Disneyland” reprise the monologue from “Sexuality.”

At least one line, meanwhile, appears to be autobiographical. Several writers have connected Prince’s lament about “why I wasn’t born like my brother, handsome and tall” to his older half-brother Duane Nelson, whose stature and athletic prowess had been a source of envy in the diminutive singer’s teenage years; alternatively, the line could be another veiled reference to Prince’s figurative “brother,” André Cymone, the target of other barbs on the What Time is It? album. Most prominently, Prince gives vent to class rage: lamenting the cab his partner in this tryst has to drive “for no money at all,” and the presumably impoverished neighborhood where she lives. Yet, as biographer Dave Hill observes, his criticisms of the rich are “carefully qualified… given the rate at which Prince’s own bank account would have been swelling at this time (it’s only the greedy ones he hates!)” (Hill 131).

Providing the enthusiastic accompaniment to this monologue is Jill Jones, Prince’s latest protégée in matters musical and otherwise. Jones had met Prince in December 1980, when she was singing backup for Teena Marie. “We were in Buffalo, New York, opening on the Dirty Mind tour,” she told Michael A. Gonzales. “Our sound check was too close to the opening of the show, and the stage was too small. Teena and I passed him in the hall, and someone introduced them. I just looked at him and smirked, saying some smart-aleck remark about the stage. I was a bratty eighteen-year-old kid, but my attitude got his attention” (Gonzales 2018 66). After the end of the tour, Prince kept in contact with the spunky young singer: until July 1982, when, Jones wrote in her liner notes for 2018’s Piano & A Microphone 1983, she officially joined his camp–though whether “that meant as a singer or a girlfriend–or both–I wasn’t entirely certain” (Jones 2018 8).

Jones’ voice is all over 1999: most notably on the title track, where she doubles keyboardist Lisa Coleman’s opening lines, as well as on “Automatic” and “Free.” But her star turn is undoubtedly “Lady Cab Driver,” where she is credited as the titular role under the enigmatic initials “J.J.” “Prince liked to have an air of mystery,” Jones told Gonzales, “so when I asked him why he put [‘]J.J.[’] instead of my name, he said, ‘Let the fans wonder who you are’” (Gonzales 2018 66). The nature of her performance certainly gave them something to wonder about.

Prince liked to have an air of mystery… so when I asked him why he put [‘]J.J.[’] instead of my name, he said, ‘Let the fans wonder who you are.’

Jill Jones

While critic Brian Morton dismisses Jones’ ecstatic screams and moans as a “relatively undemanding vocal spot,” this doesn’t seem exactly fair; being the “Lady Cab Driver” required courage, vulnerability, and a lack of inhibition, as well as an ability to sell the complex emotions with which Prince invested every (presumably) simulated stroke (Morton 2007). In its own way, it’s a fine example of what the artist later dubbed Jones’ “cliffdiver” tendency: her willingness to take risks and leap into every vocal performance, however apparently unhinged, with both feet (Dash 2016).

In fact, such is the rare combination of ardor and nuance Jones brings to this scene that many critics over the years–the majority, it’s worth noting, straight and male–have expressed discomfort over precisely what is being depicted. As Hill writes, in sharp contrast to the masochistic scenario in “Automatic,” here “it is plain that she is at his mercy. Is this a submission fantasy or a rape? Or are they just doing it right?” (Hill 131). My inclination is toward the latter. It’s easy to be overwhelmed by the intensity of Prince’s anger in the first half of the scene, which can have the effect of making Jones’ vocalizations sound like cries of fear of pain. But by the time he reaches the second half, with a telling reference to “the creator of man,” the encounter takes on a different tenor; now he’s poetic, even tender, ruminating on “the sun, the moon, the stars,” “the ocean, the sea, the shore,” “the women, so beautifully complex,” and “love, without sex.”

By the end of the verse, Prince has shaken off the anxieties that plagued him earlier in the song: “Not knowing where I’m going / This galaxy’s better than not having a place to go”–a resolution much like the one in “Moonbeam Levels,” when his narrator rejects suicide in favor of transcendence. And Jones, while unfortunately not given the same level of subjectivity as her partner, is still pretty clearly enjoying herself: she ends the scene with a contented sigh as the song shifts gears one last time, morphing into a straightforward funk jam for the rest of its eight-minute runtime.

In the end, it was that side of the song, rather than the erotic psychodrama at its center, that would be highlighted on stage during the 1999 tour. After hailing an imaginary taxi, Prince would lead the band into a high-energy rendition of the first verse, followed by a synthesizer break by Dr. Fink and a show-stopping guitar solo by Dez Dickerson; then, just as quickly, it was on to “Automatic” and “International Lover,” with the latter song’s silhouetted striptease atop an onstage brass bed providing the big theatrical setpiece of the evening.

Another short-lived arrangement, performed just once in Lakeland, Florida on February 1, 1983, trimmed even more: preserving just an instrumental vamp before moving immediately into the first verse and chorus of “I Wanna Be Your Lover,” a few bars of “Head,” and a full rendition of “Little Red Corvette.” In a sense, “Lady Cab Driver” had gone full circle, back to the simple groove that had provided the basis for “Rearrange” over a year earlier; though, never one to let a good orgasm go to waste, Prince would use a recording of Jill’s isolated vocals as the intro to “Dirty Mind” on the second leg of the tour in 1983 (see above, while you can).

Then, of course, there was “Oh Sheila”: a Top 40 hit and R&B Number 1 for Flint, Michigan’s Ready for the World, released in 1985 at the height of Prince’s “purple reign.” While not the first Prince soundalike by any means–“Something About You,” a modest hit for Memphis-based funk group Ebonee Webb in 1981, was as blatant a lift of “Head” as was legally possible–it was the most successful by some margin: even, according to legend, fooling Prince’s close collaborator Sheila E, about whom many contemporary listeners assumed he had written the track.

By divorcing “Lady Cab Driver” from its more outré elements–and, to be fair, releasing at a time when the market was primed for even the most vaguely Prince-like material–“Oh Sheila” was able to become the mainstream hit its chief source of inspiration never was. Its success, almost certainly to Prince’s chagrin, demonstrated just how pervasive the sound he’d memorialized on “Rearrange” had become in the ensuing years: from the insurgent music of “kids today” to commercial radio’s style du jour. But as any connoisseur will tell you, “Lady Cab Driver” is best experienced in its pure and undiluted form; it’s as weird, provocative, and inimitable a song as Prince ever recorded.

“Rearrange”

(Sunset Sound, 1981)

Amazon / Spotify / TIDAL

“Lady Cab Driver”

(1999, 1982)

Amazon / Spotify / TIDAL

“Lady Cab Driver / I Wanna Be Your Lover /

Head / Little Red Corvette”

(Tour Demo, 1983)

Amazon / Spotify / TIDAL

“Oh Sheila”

(Ready for the World, 1985)

Amazon / Spotify / TIDAL

Leave a Reply