Beginning with his third album in 1980, Prince had been steadily building up a mythology–occasionally bordering on a philosophy–for himself. Dirty Mind had “Uptown,” a clarion call for hedonism that eradicated all racial and sexual boundaries. 1981’s Controversy, of course, had its epic title track, a declaration of selfhood through the negation of fixed identities; as well as “Sexuality,” a return to the themes of “Uptown” with a new quasi-religious fervor. For his fifth album in 1982, he offered something even more blunt and to the point: a musical manifesto based around the four words, “Dance, Music, Sex, Romance.”

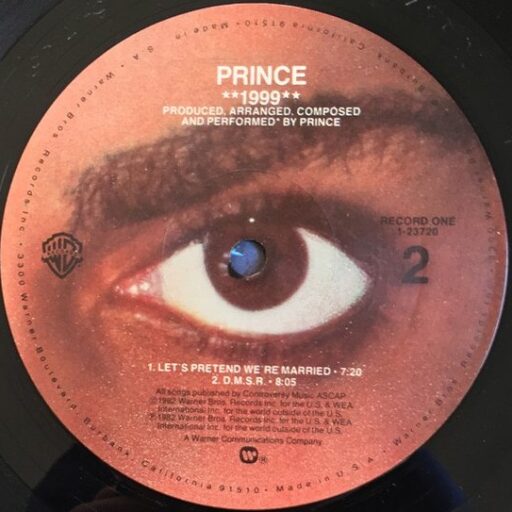

Though it was never released as a single–and was, in fact, left off 1999’s original CD release due to space constraints–“D.M.S.R.” holds a privileged position in Prince’s discography. Dance Music Sex Romance was of course the title of Per Nilsen’s 1999 biography and session chronicle, long considered definitive by fans of Prince’s mid-’80s imperial phase. It’s also, obviously, the title of this very blog, because I figured if Per’s not going to use it anymore, somebody’s got to. Its attraction to writers on Prince is self-evident: as Dave Lifton writes in his post on the song for Diffuser’s 365 Prince Songs in a Year series, “Dance. Music. Sex. Romance. Add God into the mixture and you’ve more or less got the formula for every song Prince released in his life” (Lifton 2017). Way back when I first started d / m / s / r in 2016, I posited that it would make a great title for a career-spanning collection like Johnny Cash’s Love, God, Murder, with a disc devoted to each theme.

But even the most prescient encapsulation of Prince’s guiding obsessions would have amounted to little if the song wasn’t up to snuff. Fortunately for us all, “D.M.S.R.” is an absolute banger–a paragon of stripped-to-the-chassis Minneapolis electro-funk. Like many other Prince songs of its ilk, it’s deceptive in its simplicity; a rigid Linn LM-1 beat and martial-sounding synth-horn line lay the foundation, followed by a James Brown-style turnaround and one of Prince’s now-trademark whoops. Then the main groove comes in: an inexorable lockstep of slap bass, chicken-scratch guitar, and simulated horns and percussion, executed with precision and single-minded determination.

Built atop this rhythmic base is a series of exhortations, which begin on the dance floor and–in typical Prince form–move rapidly into more lascivious territory. “Everybody, get on the floor,” he begins, “What the hell did U come here for / Girl it ain’t no use, U might as well get loose / Work your body like a whore.” In the next verse, he works in another plug for the clothing-optional lifestyle previously touted by side projects the Time and Vanity 6: “Never mind your friends, girl it ain’t no sin / To strip right down to your underwear.” But his admonitions to “Do whatever we want” and “Wear lingerie to a restaurant” also carry an undercurrent of political rebellion: in the same breath, he adds that if the “Police ain’t got no gun[,] U don’t have to run.”

Indeed, “D.M.S.R.” feels in many ways like a successor to the vision of radical, multicultural hedonism Prince first proposed in “Uptown.” Rather than simply describing a crowd of “White, Black, Puerto Rican, everybody just a-freakin’,” here he calls out each of these groups–along with any Japanese partiers in the house–directly. He even assembles his own coalition of White and Black revelers to join in with “backgroundsinging and handclaps” on the chorus: Lisa (Coleman), Jamie (Shoop), Carol (McGovney, a colleague of Shoop’s from Cavallo, Ruffalo, and Fargnoli), Peggy (McCreary), Brown Mark, and a mysterious pair identified only as “Poochie & the Count.” In an interview with Uptown magazine, McCreary recalled, “We were all out there singing and he was giving us crap, jokingly saying that ‘you white people ain’t got no rhythm,’ which I thought was funny because he had a white drummer” (Nilsen 1999 99). A gag along the same lines made it onto the album: after commanding “all the white people” to “clap their hands on the four now,” Prince gives them four measures to get on the beat before intervening and counting them in himself.

We were all out there singing and [Prince] was giving us crap, jokingly saying that ‘you white people ain’t got no rhythm.’

Peggy McCreary

Like its immediate predecessor on 1999, “Let’s Pretend We’re Married,” “D.M.S.R.” sets aside a few moments for Prince to lay out his worldview and cultivate his mystique: “I don’t want to be a poet / Cuz I don’t want to blow it,” he raps–then, his snubs at the 1982 Grammys and AMAs still seemingly fresh in his mind, “I don’t care to win awards.” Instead, he assures, “All I wanna do is dance / Play music, sex, romance / Try my best to never get bored”–a perfect encapsulation of the punkish, insouciant “Rude Boy” that was still his dominant persona. Even better is the breakdown that comes near the end of the song. After a particularly throat-shredding scream, Prince calls out his own alter-ego, the fictional engineer of Dirty Mind and producer of the Time and Vanity 6 albums: “Jamie Starr’s a thief.” Seemingly apropos of nothing, he adds, “It’s time to fix your clock”–placing a, shall we say, curious emphasis on the word “time.” He shouts out Vanity 6–pronounced “Vantitty,” because of course–then concludes the section with the appropriately juvenile kiss-off, “Now you can all take a bite of my purple rock,” before launching right back into the groove.

At the time of “D.M.S.R.”’s release, of course, both Prince and his charges were still denying his involvement in their music. The artist would famously begin a November 1982 interview with Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times by tersely “clear[ing] up a few rumors”: “One, my name is Prince, it’s not something I made up… Two, I’m not gay. And three, I’m not Jamie Starr” (Hilburn 1982). But Prince was clearly beginning to chafe beneath his self-imposed anonymity–particularly where it came to the Time, who had threatened to upstage him on the Controversy tour and would continue to do so in the months ahead. Referencing the Jamie Starr persona by name on his own album allowed him to continue the charade, while simultaneously calling attention to it: a brilliantly subliminal move of confirmation via denial.

One, my name is Prince, it’s not something I made up… Two, I’m not gay. And three, I’m not Jamie Starr.

Prince

“D.M.S.R.” ends with a curious outburst: just as Prince and his merry pranksters seem content to repeat the words “Dance, Music, Sex, Romance” ad infinitum, one of them (Lisa) calls out, “Somebody call the police,” followed by a genuine-sounding scream of distress: “Please, help me, somebody help me!” The music stops dead. Had I been asked to offer my interpretation of this moment a couple of years ago, I might have just said something about its unsettling nature–a comment, perhaps, that the fleshly pleasures Prince sings about have their dark and dangerous side. Now, though, I’m wondering if it was meant as a sly callback to the earlier joke about White people and rhythm: an uptight gentrifier shows up at a Black party, calls the cops, and shuts it down.

As both an anthem and a funk workout, “D.M.S.R.” was an obvious staple on the 1999 tour in 1982 and 1983. It would show up again as the rousing finale of the Revolution’s coming-out party at First Avenue in August 1983; as part of a short medley on the Parade tour in 1986; in minimalist form at the legendary August 1988 aftershow at the Trojan Horse in the Hague, Netherlands; and in a segue with “Controversy” on the 1990 Nude tour. Personally, I’ll always remember it as a highlight of the Musicology shows in 2004, where the horn-heavy NPG lineup (complete with Maceo Parker on sax) brought out the elements of organic funk that were always there beneath the synthesizers and drum machines.

However its arrangement changed, though, one thing at least stayed the same: “D.M.S.R.” was Prince’s calling card–a four-word (four-letter!) summation of everything he and his music were about. It wasn’t the first time he tried to sum himself up in song, and it wouldn’t be the last; but I’d be hard-pressed to come up with another time when he said as much in quite as few words.

(Thanks to D Merle on Twitter for the head-slappingly obvious correction that the line is “All the white people clap their hands on the four,” not “on the floor” as I originally wrote. I am getting my ears cleaned forthwith.)

Leave a Reply