Tag: tiffany entertainment corporation

-

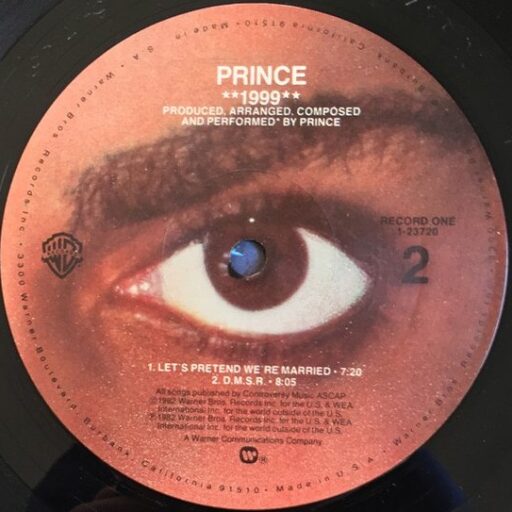

Baby

Prince’s silky falsetto vocals and baroque musical accompaniment sound straight out of the Philadelphia-based “smooth soul” playbook–with the obvious caveat that, while Philly soul employed teams of session musicians, vocalists, producers, and arrangers, the vast majority of “Baby” was recorded by Prince himself.