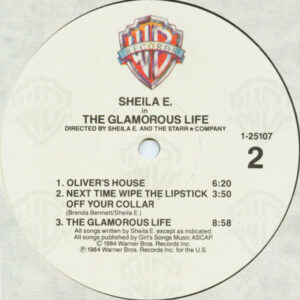

When Sheila E.’s debut album came out in early June of 1984, it was packaged as a kind of aural movie, with Sheila as its breakout star. The front cover presented the artist and title in the style of a lobby card or theater marquee: “Sheila E. in The Glamorous Life.” The back cover framed the album’s contributors as “cast” and crew, with “Sheila E. and The Starr ★ Company” as co-directors, Larry Williams as “Director of Photography,” and credits for “wardrobe” (Louis & Vaughn, Marie France), hair (Earl Jones), and makeup (Jayson Jefferys). Even the two sides of the vinyl record and cassette tape were labeled “Reel One” and “Reel Two.”

This presentation was appropriate; The Glamorous Life is a cinematic record, if not in the sense of telling a complete story. It’s more like an anthology film: A collection of vignettes, each with its own cast of characters, narrative, even genre. And kicking off “Reel Two” is “Oliver’s House”–Prince’s own take on the teen comedy genre that was entering a golden age in mid-1980s Hollywood thanks to movies like Amy Heckerling’s Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) and, soon, the filmography of writer/director John Hughes.

Like many of the songs destined for The Glamorous Life, “Oliver’s House” started life as an instrumental recorded at Sunset Sound. Prince cut the basic track on January 5, 1984: the same session where he, Lisa Coleman, and Wendy Melvoin recorded the as-yet-unreleased “Be My Hero,” which sessionographer Duane Tudahl describes as a “slow, moody instrumental,” possibly intended for the Purple Rain movie score and distinguished by Lisa’s closing quip, “OK, it’s to the glue factory!”1 It’s unclear whether the Revolution dyad played on both songs: Prince Vault credits Prince for “all instruments, except where noted” on “Oliver’s House,” though its sprightly keyboard hook and simmering rhythm guitar sound like they could be the work of Lisa and Wendy.

The next day, Prince returned to the studio with lyrics and a title, along with some doodles to elucidate the song’s concept; Tudahl describes a reference to “a neighborhood slut” named “Glodean,” and a sketch of “a castlelike house… complete with stick figures playing in a swimming pool.”2 Not that the concept needed much elucidating: It’s a simple tale of anticipation and payoff, as our narrator catches wind (from the aforementioned “neighborhood slut,” no less) of a rager being held at the titular domicile. She thinks back to the party Oliver threw “last June,” when “his girl Louise… got drunk and called [her] a bitch / Just ’cause [she] kissed him.” Cut to this year’s party, where she and the other guests “take turns throwing down” in the pool, then “throwing up” in the bathroom. Finally, Oliver takes her to “his mother’s room,” “dress[es her] up” in his mother’s “fine clothes,” and “undress[es her] slowly.” See? Simple!

“Oliver’s House” shares its high school milieu with “Wet Dream” by Vanity 6, and its title character would soon reappear in the lyrics of “In a Spanish Villa,” both of which suggest that it was written with Apollonia 6 in mind; but it’s ultimately a richer text than either of these loose connections. Its adolescent social commentary is more sharply defined than that of “Wet Dream,” with its anachronistic “soda shop” iconography; the line in the chorus about playing with “the white boys,” in particular, acknowledges race and class hierarchies that were rarely made so overt, either in Prince’s mid-’80s songwriting or in the Hughesian teen movie canon. As for Oliver himself, while “Spanish Villa” would later flatten him into a “Latin lover” archetype, here he has a specific eccentricity that can’t help but feel like a self-insert character: A “weird” guitarist with multiple girlfriends, a piano in his bathroom, and an Oedipal complex? They may as well have called the song “Prince’s House.”

Also punching well above its weight is the song’s arrangement, which holds its own among the most playful and inventive of Prince’s storied 1984 output. In his special presentation at the 2023 #TripleThreat40 symposium, veteran music writer and producer Dan Charnas called “Oliver’s House” a “symphony of restraint,” building up from just a few basic elements: a phased kick, snare, and clap pattern on the Linn LM-1; a clipped, “nursery rhyme”-like keyboard line (later doubled by the vocal melody); and a gurgling bass synth. Prince is also playing bass guitar, but mainly as a percussive instrument, muting the strings and holding his rare “sounded notes” back for strategic deployment. When his (or Wendy’s) rhythm guitar comes in on the chorus, it’s similarly “curtailed” to a single, trilling chord. The piano solo that closes the second chorus and recurs later in the track consists of just four notes, ending with little fanfare.3

[Prince] sang what he had in mind and he said, ‘Come up with some kind of cheesy melody, what have you got?’

David Coleman

Having laid this rudimentary musical foundation in the first third of the song, Prince spent the remaining two-thirds subverting it. First, just as he did for “The Glamorous Life”–on the same date, in fact–he brought in Lisa’s younger brother David Coleman to add cello to the track. “He sang what he had in mind and he said, ‘Come up with some kind of cheesy melody, what have you got?’” Coleman recalled. The string player’s first idea was a line played pizzicato, or plucked, rather than using the bow, but “Prince said, ‘Not that one.’” So instead, he improvised a minor-key “variation” on Don A. Ferris’ orchestral theme for the 1950s sitcom Father Knows Best.4 Prince would use this passage to “score” the moment when the action moves to Oliver’s mother’s room, its warped take on midcentury domestic nostalgia adding a veneer of irony to the scene. At the same time, its clashing key evokes a distinct sense of unease: the aural equivalent of a canted angle in cinema.

Less dramatic, but still effective, is the series of smaller gags that offer a kind of running commentary on the lyrics. The line about the “piano in [Oliver’s] bathroom” is met by a few plonking notes on the piano–which then absurdly reprise after the line, “he knows how to play guitar.” Meanwhile, the line, “We take turns throwin’ up” is punctuated by Coleman’s cello deftly imitating the sound of someone hurling into a toilet bowl. When we reach the line, “I’m a sucker for a major c(h)ord”–besides working as an oblique double entendre for the size of Oliver’s, ahem, stack of wood–it’s a cue for the minor-key cello to drop out of the mix, returning the song to a literal “major chord.”

These moments of whimsy serve as evidence of the burgeoning psychedelic bent in Prince’s music circa 1984, a development all the more impressive for his avoidance of overtly retro sonic signifiers. Even the deliberately simplistic chorus functions as a kind of musical prank, with an exclamatory “Fun!” on the “one” of each measure–an allusion, almost certainly, to the similar construction of Sly and the Family Stone’s 1968 song by that name–serving as one of the few elements that break up the monotony of the verses. By the end of the song, that “Fun!” is all that remains of the refrain: a drumbeat of wanton revelry.

Prince tinkered with “Oliver’s House” for the rest of the first week of 1984. On Sunday, January 8–the same day he cut the basic track for “17 Days”–he even tried adding a harp to the song; he wasn’t happy with the session player’s performance, though, so he ended up saving that musical idea for the re-recorded “Possessed.” Ultimately, as with “The Glamorous Life” a month later, it was the addition of Sheila’s percussion on Monday, January 9 that made the song complete. She enters the track at about the halfway point, playing a cowbell pattern familiar from the Time’s “Jungle Love” and as-yet-unreleased “Chocolate”; then, after a few minutes of vamping over the minimalist synth, piano, and cello, she launches into a timbale solo that dominates the last 30 seconds. It is, argues Charnas, “the one virtuoso performance in the song”: The moment when Prince finally releases the tension he’d been rigorously building for the last six minutes and gives his newest star license to cut loose.5

Perhaps because of the apparent frivolity of its premise–or just the surfeit of classic material Prince was turning out in early 1984–today “Oliver’s House” is a bit of a buried gem. It certainly wasn’t destined for radio play: Its only non-LP release was in early 1985 as the B-side of “Noon Rendezvous,” the last and lowest-charting of the singles from The Glamorous Life. It was at least a staple of Sheila’s opening slot on the Purple Rain tour, though its maximalist live arrangement was a far cry from the studio version’s vaunted restraint, with added musical phrases and timbale breaks, frenetic soloing by saxophonist Eddie M., a call-and-response of “I’m gon’ be in Sheila’s house,” and even a series of false endings straight out of Prince and the Revolution’s “Baby I’m a Star” playbook. Me, I prefer an intimate gathering to a wild bacchanal; so if the “Oliver’s House” fandom is to remain an invite-only affair, that suits me fine.

(Featured Image: Sixteen Candles, John Hughes, 1984.)

Footnotes

- Duane Tudahl, Prince and the Purple Rain Era Studio Sessions: 1983 and 1984 – Expanded Edition (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), p. 217. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 218. ↩︎

- Dan Charnas, “Human Time, Machine Time: Prince and the LM-1 (Part 2 of 2),” originally presented at #TripleThreat40, New York University, April 2, 2023; Vimeo, April 16, 2023. ↩︎

- Tudahl, p. 218. ↩︎

- Charnas. ↩︎

Leave a Reply